Aike-Dellarco (Building 6, 2555 Longteng Avenue, Xuhui district, Shanghai, China), Sept 6—Oct 6, 2016

Hu Yun’s work tends to go hand in hand with research, surveys and travels, and revolve around some specific people; he extracts—from museums, archives and oral histories—certain fragments from people’s lives, and eventually displays these in some form. In the exhibition “The Malaise of Narrative” at the new West Bund Aike-Dellarco space, the artist placed all these people in one exhibition hall in a way rarely seen. They are, respectively, the artist’s grandfather, missionary Saint Francis Xavier, explorer Robert Sterling Clark and his cohort, as well as British East India Company employee and amateur naturalist John Reeves. Therefore, apart from showing the “material evidence” about these people’s lives as usual, this exhibition also discussed the relationship “between” the individual pieces of work. It was the artist’s re-contemplation of his creative work in recent years.

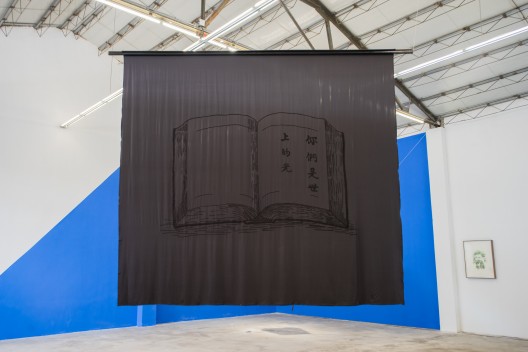

This point is hinted at by the embroidery installation in the middle of the exhibition hall—onto the embroidery are inscribed exquisitely the characters for “You Are the Light of the World”. This image came from a square scarf that Feng Yuxiang gave to Sun Yat-sen as a gift in the 1920s. The artist found it in a museum, and commissioned a master of Suzhou embroidery to spend seven months enlarging it to the current size. The character “you” demonstrates the “plurality” of the common people; such plurality eliminates differences in national origin, ethnicity, and faith while retaining only “human” characteristics. Despite the fact that the persons coming from Hu Yun’s pen—if we deem his work a special type of writing—tend to have extraordinary experiences or misfortunes, in the artist’s continuing description, their life paths sometimes intersect with those of others’—even with an astounding level of structural overlap. These characters are like isolated islands separated from the world to which the artist pays a periodic visit, at times making new discoveries on his way back and forth, and at other times bringing something from “here” to “there”; gradually, the two become cousins, and their relationship further deepens.

But the artist does not mean to encapsulate these characters in a particular form; on the contrary, due to the juxtaposition “between” the pieces of work, a net-like narrative structure is gradually constructed whereby these characters and happenings are intertwined, ready for the viewers to saunter through. This form further prevents the possibility of a singular narrative, and yet we are not certain where these endless possibilities will lead the artist and viewers. Just as history is invariably intermingled with imagination, fallacies and lies, it is no different here. The title “The Malaise of Narrative” is meant to imply a looser form of narrative with softer borderlines, rather than the type of full-on obsessive mania for fixed narrative that is currently in vogue.

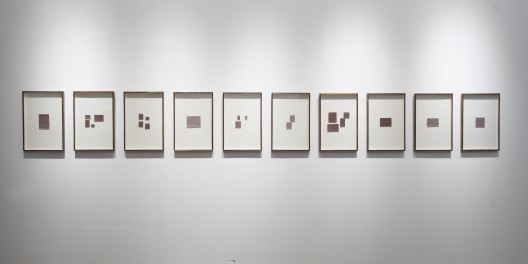

Hu Yun will often treat an artwork as the starting point or source material for his next piece of work. During this process, his work undergoes constant transmutation, turning the preceding piece into “material evidence” of the artist’s own career. In this sense, the artist himself in turn becomes the “phantom” of these “phantoms” of historical residue. “Everything is possible in darkness II” (2016) is the evolution, or rather erosion, of an earlier version by him. Originally vague information has been completed wiped from the new version[1]. Viewers face the virtual shadows shrouding the surface of the photos, just as they face fading history. What the viewers miss in reading the photos they can peruse in the supplementary notes in “Fate” and “As Light as a Piece of Paper”; the installation composed of salt crystals and typeset letters then turns these virtual shadows into a monumental type of work. To take another example, for the saddle installation in the middle of the exhibition hall, the artist places a yoga mat used in his 2014 project at the Guangzhou Times Museum right under the saddle, which aptly outlines the identity of the Indian explorer who died during the 1908 exploration of Shaanxi and Gansu provinces[2]. Take yet another example, those several exquisite paintings of palm trees—they initially existed independently, reflecting the artist’s imagination of the exotica of Southeast Asia; but now they become, fittingly, part of the story about Shangchuan Island[3]. These, along with the white pebbles the artist picked up on this small southern Chinese island and enlarged, constitute a certain image of Shangchuan Island.

The artifacts in the exhibition thus more or less represent selected moments in these four people’s lives. Some are stationary moments—the journeys of the Spanish missionary and Indian explorer terminated by death: the end of action; others are midway along life’s journey—the colonizer and naturalist packing the pheasants and preparing to ship them back to Britain, and the Chinese serviceman fighting in adverse circumstances. Hu Yun provides viewers with one chapter, leaving them to fill in the missing parts with their imagination. To the artist himself, it appears just the same.

《黑暗中什么都可以发生》,摄影(一套10个),40×60 cm (每个),独版,2016 / Hu Yun, “Everything is possible in darkness” photographs, 40 x 60 cm each, 2016

《你们是世上的光》,在黑色丝绸上刺绣,300×250 cm,2015 / Hu Yun, “You Are the Light of the World”, embroidery on black silk, 300 x 250 cm, 2015

《无题(棕榈树 )No. 2》,纸本水彩,76.5 x 56 cm,84 x 63.5 x 7 cm (带框),2014 / Hu Yun, “Untitled (Palm No. 2)”, watercolor on paper, 76.5 x 56 cm, 2014

《薄如纸》,金属中国字符,灯箱,201.5 x 80.5 x 12 cm,2015 / Hu Yun, “As light as a piece of paper”, Chinese metal characters, lightbox, 201.5 x 80.5 x

12 cm, 2015

[1] In “Everything is possible in darkness I” (2012), the artist collaborated with his grandfather for the first time. He selected photos from ten different periods of his grandfather’s life for display. But on the exhibition site, the viewers were only able to see limited scripts on the back of the photos. This time, the artist skipped the developing process while remaking these photos, thus, the images disappear completely after being shown for a fleeting moment.

[2] This piece of work was based on an exploration of the geographical features of China’s Shaanxi and Gansu provinces in 1908 organized by Robert Sterling Clark, an American. One day during the exploration, an Indian member was found missing. Then came the bad news—this Indian member, while practicing yoga in front of local residents, was regarded as heterodox, and was killed in the ensuing conflict. The expedition was pronounced over due to this unexpected tragedy.

[3] Shangchuan Island is the small island in southern China where Spanish missionary Saint Francis Xavier (1506-1552) spent the last moments of his life. It is located 200 km from Guangzhou. He had attempted to stow away and land stealthily in China, but died suddenly from illness. Due to his remarkable achievements as a missionary in the Far East and his intent to preach to China, he was praised by the Vatican and canonized.