Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 5th Ave, New York, NY, US), Dec 11, 2013 – April 6, 2014

Five years in the making, it’s finally open to the public in last December.“Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China” attempts to be a defining show on the subject, charting out new identities for Chinese contemporary art by featuring artworks embodying the “ink art aesthetic,” yet it is the “Ink Art” aesthetic wherein lies the problem of this show. “Ink Art” though full of iconic work, fails by looking at contemporary work merely through the prism of “tradition,” thus largely obfuscating the contemporary meanings and influences which anchor the work.

As Maxwell K. Hearn, the head of the Asian Art Department at the museum and curator of this show, elucidates in the exhibition catalogue, “Ink Art examines the creative output of a selection of Chinese artists from the 1980s to the present who have fundamentally altered inherited Chinese tradition while maintaining an underlying identification with the expressive language of the culture’s past.” Even though the primacy of the “ink art” tradition in China has increasingly been challenged by the idiom of Western art as well as that of new media ever since the early twentieth century, some Chinese artists chose to retain traditional Chinese painting medium or a “brush and ink” aesthetic in their practices.

Qiu Zhijie’s “30 Letters to Qiu Jiawa” and Yang Qiuchang’s “Crying Landscape” are embedded in the Met’s permanent collection of ancient Chinese art.

邱志杰的《给邱家瓦的30封信》和杨洁苍的《会叫的风景》在大都会博物馆古代中国艺术陈列展厅展出。

Viewing the works of Chinese contemporary art included in this exhibition as “part of the continuum of China’s traditional culture,” the curator has embedded and contextualized the entire “Ink Art” show in a traditional setting. As viewers enter into a gallery near the Great Hall, they are greeted by two sets of large-scale triptychs, “30 Letters to Qiu Jiawa”(2009) by Qiu Zhijie and “Crying landscape”(2002) by Yang Jiechang, installed next to a Dunhuang mural and some ancient Buddhist sculptures from the museum’s permanent collection of traditional Chinese art. Having adopted the styles of traditional scroll ink painting and “blue-and-green” landscape painting, Qiu and Yang’s works seem to merge right into the larger context, camouflaged among the permanent pieces on display that were created more than 1,000 years ago. Qiu’s work depicting the iconic Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge has a contemporary edge to it, however; festooned with hovering symbols of spiral shapes, ladders and an infant figure, it serves as a visual narrative of the suicides facilitated by this glorious national symbol and the collective memory associated with it. Yang Jiechang takes similar aim at architectural icons with overlapping images of mysterious explosions in front of the Houses of Parliament, an oil refinery with smoke rising into the blood-red sky, a missile aimed over the Three Gorges Dam, the Pentagon under terrorist attack and a surreal Las Vegas skyline occupied by famous New York landmarks—all these images testifying to the idea that established power structures could be in imminent danger, and overthrown overnight. The subversive commentary embodied in the two contemporary works serves as a dystopian force, pulling the viewers immediately from the “ancient heaven” back the reality.

En route to the main displays, three other works are embedded in a gallery which primarily features ancient artifacts and figurines from China. A set of six prints displayed in a glass case attached to the wall resembles the maps directly torn out of antique woodblock-printed books; however, the ubiquitous misnomers, cartoon-like markings and geographic misrepresentations reveal that they are the work of contemporary artist Hong Hao and his alternative interpretations of our contemporary world and it’sglobal trends. In these maps, the international influences, military power, prevalent value systems and associated stereotypes of different geographic regions are visualized and communicated to the audience with irony and playfulness. Overlooking Hong Hao’s maps are two signature Ai Weiwei works—a mosaic-like map of China constructed from the wood salvaged from a destroyed Qing dynasty temple and a Han-dynasty jar painted over with a Coca-Cola logo. Placed in the center of a permanent collection gallery, these three works are meant to show how Chinese contemporary artists confront or comment on China’s self-image or national identity. However, given their respective media and the context of the stated curatorial aims of “Ink Art,” their relevance to the organization of the entire show is questionable.

In a gallery showing ancient Chinese artifacts and figurines, a set of six prints from Hong Hao’s “Selected Scriptures” are on display with Ai Weiwei’s “Map of China”. Ai’s Han Dynasty jar overpainted with Coca Cola logo is on view in the same gallery as well.

在展现古代中国工艺品和小雕像的展厅内,洪浩《藏经》系列中的一套6件版画和艾未未的《中国地图》与涂有可口可乐标识的汉代陶罐作品一同展出。

The overarching idea of interpreting Chinese contemporary art through the lens of traditional Chinese aesthetics is also evident in the exhibition’s display and overall structure. Exhibited in the galleries that were originally designed to recreate an authentic, traditional Chinese setting—notably Astor Court—the famed Ming Dynasty-style courtyard—and the Douglas Dillon Galleries—almost all the contemporary works are placed in wood-and-glass vitrines made specifically to show scroll paintings and calligraphy works. Thematically, this exhibition is organized into four main sections—“The Written Word,” “New Landscapes,” “Abstraction” and “Beyond the Brush.” These titles immediately associate with quintessential art forms from China’s past. In the wall text for each section, the curatorial statement always starts with, and invariably weighs towards, an explanation of the aesthetic traditions and ethos central to the traditional art form. Taking the “New Landscapes” section as an example, the statement begins with, “Over the past one thousand years, landscape imagery in China has evolved beyond formal and aesthetic considerations into a complex symbolic program used to convey values and moral standards. In the eleventh century, court-sponsored mountainscapes with a central peak towering over a natural hierarchy of hills, trees, and waterways might be read as a metaphor for the emperor presiding over his well-ordered state…” These statements often end by noting that many Chinese contemporary artists nowadays have drawn inspirations from these “past models,” seemingly justifying the exhibition’s thematic categorization based on the contemporary works’ connection to their precedents.

Zhang Jianjun’s purple scholar rock made from silicone rubber is displayed in the famous Astor Court

在著名的阿斯特庭院内张健君用硅橡胶做的紫色太湖石

But the question remains: is this new curatorial perspective used in the Met’s Ink Art show really valid? As we ponder the approach of using “past models” of Chinese art as a vantage point from which to interpret the recent development of Chinese contemporary art, several problems arise.

First of all, the entire exhibition is conceived and curated based on an underlying assumption made by the curator—that the same set of criteria that were developed to appreciate ancient and traditional Chinese art could be readily adopted to similarly judge contemporary Chinese art. This assumption is a fundamental fallacy of this show. If we carefully consider all the social upheavals and artistic transitions that China has gone through in the past several decades, it is clear that the development of Chinese artistic traditions cannot be viewed as a linear narrative. Since the categorization of contemporary works under each theme is primarily determined by their relevance and resemblance to different traditional art forms in material, style, technique and visual trait, the exhibition only reveals the most superficial connections between the traditional and contemporary. The real complexities behind the recent development of Chinese contemporary art, such as important social, political, economic and cultural changes, remain veiled. By highlighting and framing contemporary Chinese art in this manner, this exhibit draws viewers to focus more on techniques and less on the real message behind the individual works.

In addition, since it is specifically dedicated to the examination of “ink art aesthetics” in Chinese contemporary art, “Ink Art” almost provides a panoramic view on how traditional formats and mediums are continuously adopted or re-appropriated in Chinese contemporary art to further a variety of artistic agenda.

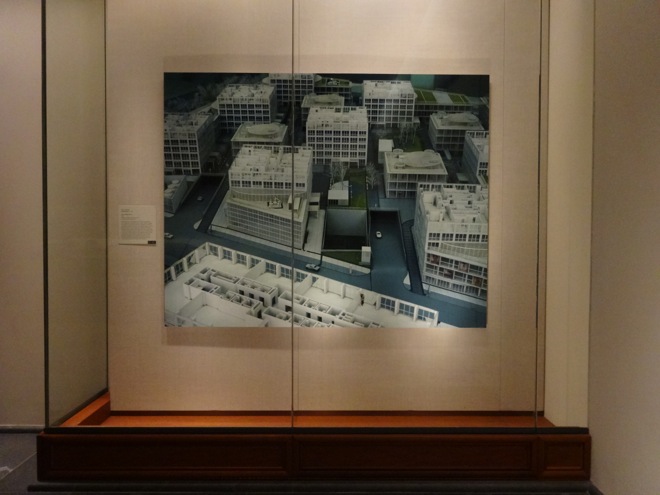

Credit must be given to the Met, as the exhibition’s wide selection of works allows many unfamiliar Chinese names exposure on an institutional level in the West. Nonetheless, this raises a side issue as well—some of the works exhibited have little relevance to the themes they serve and thus the exhibition sometimes wanders off topic. The section “Beyond the Brush,” features works which, in the words of the curator during a press preview speech, he “could not resist acquiring, but have nothing to do with ink.” To be more specific, these works do not use ink itself as a medium but embody the ink aesthetic, as their forms are inspired by traditional artworks that derive from Chinese literati pastimes or patronage. As general and vague as the statement sounds, the exhibition’s expansion of focus in the last section raises an issue of cohesiveness. For example: “Ruyi” (2006), a ceramic mutation of the most iconic talisman in traditional Chinese culture made by Ai Weiwei, is on view here. This fungus-shaped scepter being transformed into a lump of human organs by the artist looks both odd and disturbing. By doing this, Ai dramatically subverts the traditional talisman that symbolizes power and longevity into a vulnerable, monster-like creature. Coming from a lesser-known series made by Ai, “Ruyi” itself is an interesting selection. However, since the work’s traditional prototype itself is so remotely related to the “ink art aesthetic,” its inclusion in the exhibition seems farfetched. For the same reason, the inclusion of Hong Hao’s map, Ai Weiwei’s Coca-Cola jar and mosaic map is doubtful as well. In the “New Landscapes” section, an image of isolated concrete jungle rendered from a real-estate architectural model by Xing Danwei, “Urban Fiction No. 13”(2005), is on display next to a ghostly photograph of Shanghai by Shi Guorui. As these works bear no noticeable elements of Chinese ink tradition, their inclusion in the show should be questioned.

Xing Danwen, “Urban Fiction No.13″ (2005), digitally manipulated chromogenic print.

邢丹文,《都市演绎No.13》(2015),C print。

That said, the exhibition does feature many historically important classic pieces including Zhang Huan’s “Family Tree” (2001), the photographs of Song Dong’s most famous performance “Printing on Water” (1996), Sun Xun’s video “Some Actions Which Haven’t Been Defined Yet in the Revolution” (2011), Cai Guoqiang’s 1993 performance “Project to Extend the Great Wall of China by 10,000 Meters,” and Xu Bing’s installation “Book from the Sky”—the zen-like atmosphere created by Xu Bing’s installation leaving a deep impression on many viewers. Along with these iconic works, one of the highlights in the show is Huang Yongping’s “Long Scroll” (2001). Adopting the format of a traditional paper scroll, Huang gently depicts several of his installation projects created between 1985 and 2001 and rendered in simple palette of orange and blue watercolor. These casually illustrated images could be viewed as informal archival documentation or even a “mini-retrospective” of Huang’s past projects. Here, the feeling of the grandiose installations is replaced by a sense of intimacy between the images and the viewers.

Zhang Huan’s “Family Tree” on view with Song Dong’s “Printing on Water (Performance in the Lhasa River, Tibet, 1996)”

张洹的《家族树》(2001)与宋冬的《印水》(西藏拉萨河上的行为表演,1996)

Right before the beginning of 2014, two well-respected art institutions in the U.S.—the Rubell Family Foundation and the Metropolitan Museum of Art—both opened their first landmark exhibitions featuring Chinese contemporary art. While the “28 Chinese” exhibition at the Rubell Collection clearly places more emphasis on the young generation of Chinese contemporary artists and their individual practices, “Ink Art” has taken on the ambition to examine new collective identities for Chinese contemporary art, viewing this art from the standpoint of its own cultural heritage instead of the Western-avant-garde artistic language the artists have adopted. While both exhibitions have attracted much attention within the art world both locally and globally, their respective differing ways of framing and interpreting Chinese contemporary art brings up the important point of cultural representation of Chinese contemporary art.

“As the debates of recent years have shown, ‘identity’ is not an ‘essence’ than can be translated into a particular set of conceptual or visual traits. It is, rather, a negotiated construct that results from the multiple positions of the subject vis-à-vis the social, cultural, and political conditions which contain it,”[i] as Mari Carmen Ramirez, the renowned Latin American art curator, argues in her essay “Brokering Identities.” Unequivocally, the Met’s strong collection of traditional Chinese art, the curator’s particular expertise in traditional Asian art, good intentions and academic ambitions are all evident in the curatorial decisions, making this show a strong showcase of iconic pieces. However, the idea of using the “ink art aesthetic” to characterize and examine the pieces being shown is problematic. Overly emphasizing the visual traits shared between traditional and contemporary Chinese art – such as materials, techniques and artistic forms – “Ink Art” has unintentionally fallen into the Orientalist trap.

[i] Mari C. Ramirez, “Brokering Identities: Art Curators and the Politics of Cultural Representation, ” in Thinking about Exhibitions, ed. Reesa Greenberg et al. (New York: Routledge, 1996), 23.