Press the Button – Leung Chi Wo: A Survey Exhibition

OCAT Shenzhen (Exhibition Hall A, Building F2, Enping Road, Overseas Chinese Town, Nanshan District, Shenzhen, 518053, China), April 25 – June 30, 2015

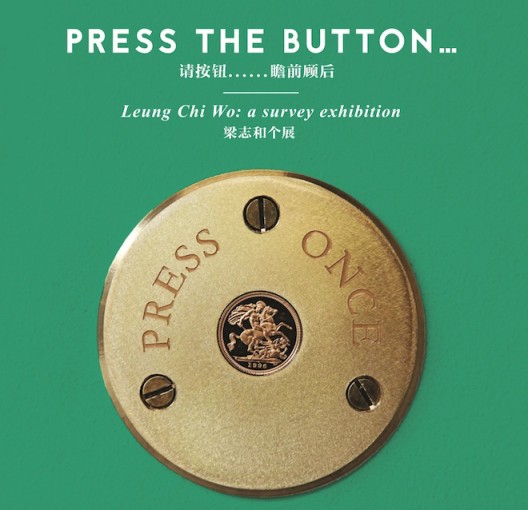

Printed beneath the exhibition title on the bright green background of the exhibition poster is a round brass disk set with three rivets which appears to be fixed to something. The words “Press Once” are etched into the brass disk inlaid with a British coin minted in 1996; the coin depicts St. George and the dragon. In 1996, Leung Chi Wo helped found one of Hong Kong’s most important and vibrant independent art spaces, Para/Site. Connections between events occurring within the same year are but one type of relationship to be found in amongst personal histories and reality’s complex network. Leung Chi Wo’s artistic practice over the last two decades has revolved around pursuing and presenting the various associations embedded in these complex connections. Curated by Carol Yinghua Lu, “Press the Button—A Survey Exhibition” is the largest solo exhibition in Leung Chi Wo’s artistic career thus far, presenting 31 works the artist created between 1993 and 2015.

For the show, OCAT Shenzhen’s long, rectangular exhibition hall has been segmented into several open spaces. Each work is arranged so that viewers can choose to focus all of their attention on the piece before them, or turn to see other pieces behind or beside them. Thus, different areas are linked together by the wandering of the viewer’s eye, transforming the exhibition space into an open network of interlinked art.

Before I attended the exhibition, I went to hear a dialogue between the artist and the curator. Leung Chi Wo looked to be in his thirties, with a shaved head and heavy strains of Cantonese in his Mandarin. His speaking voice was quiet, permeated with an inner calm. He began by talking about frequent trips from Hong Kong to Shenzhen with his mother for the low cost health care available on the Mainland, and the way his memories from those experiences informed his newest piece in this exhibition, “Shenzhen Mine 1973”. Leung says: “This piece is very fragmented. It contains many elements from 1973—my medical record card, a map of the route from Lo Wu Control Point to Bao’an Hospital, the cover of an issue of China Pictorial, a one fen coin, art textbooks published in Mainland China, etc. ‘Mine’ is a double entendre referring to both ‘myself’ and ‘mining’, because the exploration of memory is an excavation process to me.” When the viewer does as the exhibition title commands, a single press of the one fen coin button turns on strains of ambient music which pluck gently at the emotions, and sets an old fashioned electric fan whirring. The fan blows open the China Pictorial cover, and the projection light hidden by the miner’s lamp depicted on the magazine cover casts images of Shenzhen’s streets and sky onto the opposite wall. The fan blows as long as the viewer’s finger presses down on the button; as soon as it is released, tranquillity gradually settles over the space once more.

《我的深圳矿藏1973》,装置 摄影,激光篆刻有机玻璃,录像投影,电风扇,旧杂志封面,旧硬币 尺寸可变,2015

“Shenzhen Mine 1973”, installation, Photos covered with laser engraving on plexiglas, video projection, electric fan, old magazine cover, old coin as press button, Dimensions variable, 2015

Pressing buttons has become an indispensable action in our lives—an action nearly as ubiquitous as “flipping a switch”. Buttons start our computers, microwaves, elevators, mobile phones, and we push buttons to ring doorbells. City life is immersed in physical and virtual button interfaces; we touch them when we purchase metro tickets, check in for flights, take passport photos, etc. Buttons trigger the opening of secret doors in all kinds of action and adventure movies; this association can be extended to combination locks and the hacking of security and defence mechanisms. For Leung, the “button” is a physical manifestation of the 1973 which exists in his imagination, while the associations arising from pressing the button, the resultant sense of expectation, and what actually happens after the button is pressed can be unexpected. “In 1888, Kodak released a revolutionary invention: a portable camera which completely democratized photography. At the time, their slogan for this product was, ‘You press the button and we do the rest.’ This sentence seemed to tell people they need no longer concern themselves with the relationships between things. The button is an extremely important component of photography. To me, it’s not just a media tool; it’s also a concept, an involvement of media. The button is part of social development, an expectation—but even more so, it is a nexus for our interactions with another time. At the press of a button, I can create a relationship with 1973, a real relationship.”

This piece epitomizes Leung Chi Wo’s creative practice. As Leung says in a self-evaluation of his work, “I am an extremely rational person. I only work on a piece if I’m convinced there are many reasons to do it.” In a single work, the artist has involved a play on words, the arrangement of space, the shape of the sky, changes in the perception of social spaces over time, personal observations and memory, and constructed a relationship with the viewer. These multidimensional threads run throughout Leung Chi Wo’s creative practice, referencing and influencing each other. Leung is optimistic about the viewer’s reaction, “I’m very interested in complex hierarchies, and I want to share them with the audience. It is truly difficult to find complex networks without a piece, but it’s also so difficult to express them through art…. There are many kinds of artists; viewers are heterogeneous too. There are so many different kinds of people in the real world, so there must be a few like me…. I’m curious though, I keep trying to understand other people’s realities.”

Similarities and differences between people and the connections that form and extend between them are especially apparent in Leung Chi Wo’s “Domestica Invisibile Series”. From 2004 to 2007, Leung visited 80 households—some he was familiar with, and others he was a stranger to. Through the camera lens, Leung attempted to seek out and capture individual lives and the temperature of memory contained within these private spaces. After the completion of the project, Leung found himself thinking about the people he had visited, and kept track of their lives through the internet. “Without a doubt, the development of my work has an important relationship with the daily progress of technology. The advent of the internet is a part of my personal narrative and growth. I remember the profound experience of sending my first email. I remember setting up my email address and sitting in front of the computer that entire day, waiting for someone to send me a message. The internet closed vast distances. I spent a lot of time online…. I often wonder what people I used to know are doing.” When Leung searched for the American art critic Jonathan Napack and multimedia artist Hiroaki Muragishi, he found out they had already died. Leung’s “Jonathan & Muragishi Series” was a reconstruction of his memories of the two through a number of scattered elements including photographs taken during the “Domestica Invisibile” project, recordings of the artist reading the notes he took from conversations with the two, a stuffed toy peeking out from inside a cabinet, and the DVD resting on top of it. “That DVD was a film called Monkey Love, Muragishi’s voice was featured in it. When you listen to the recording, it’s as if he’s still alive; it’s a bizarre feeling, as if the cabinet is locking in his existence.” Through sound, furniture, images, spatial arrangements that reference the home environment and text, what Leung has recreated is a rich narrative of history from an individual perspective. “History is full of inaccuracies, and if history can be inaccurate, it leaves a lot of space to discover other inaccuracies.”

《家居隐事系列》(局部),摄影,120×150 厘米,2004-2007

“Domestica Invisibile Series”(detail), photography 120 x 150 cm, 2004-2007

《降落伞与村岸系列》,摄影,彩色照片,120×150厘米,2008

“Jonathan & Muragishi Series”, photography, C-print, 120×150 cm, 2008

There were seven pieces missing from the opening ceremony of this exhibition due to “logistical issues” relating to Chinese customs. One of the missing pieces was “Bright Light has Much the Same Effect as Ice”. This piece was exhibited in the 2012 Guangzhou Triennial. In the installation, a two jiao Hong Kong coin from 1893 is the button that switches on a refrigeration unit; viewers can then experience conditions mimicking the temperature in Hong Kong on January 18th, 1893, which both the China Mail and the Hong Kong Observatory reported at as low as -4°C—a truly abnormal temperature for Hong Kong’s subtropical climate. The viewer sees a black and white photograph marked with the words, “I saw what you saw what he saw”; looking into the eyes of one of the men being photographed, the viewer might attempt to seek out that same photographer, who claimed to have photographs of a Hong Kong covered in snow which were never publicized. The work behind the British coin depicted in the exhibition poster “Untitled (Love for Sale)” is also set against this type of historical research. The piece recalls Hong Kong media coverage of the rise and fall of politics and the economy in Manchester, and was shown at the Asia Triennial Manchester 2014. Its button controls the rise and fall of a three meter stack of newspapers situated at the center of a stage, alluding to the similarities between politics and spectacle.

Leung discovered there were hardly any contemporary artists working in Hong Kong for the first few years following his return from his studies in Europe. Though he never had any ambitions to become an artist, a series of fortuitous events led him to devote his entire career to art. With his surroundings as a departure point, Leung excavates and tells the individual stories happening around him through an approach combining internet searches, research, in-person interviews and field work. Not only does Leung personally practice the belief that “history is what happens around us”, he also brings his students along with him. For “Untitled (Words about Memories but Not Exactly)”, Leung and his students spent six months finding all of the artists mentioned by name in Hong Kong’s art history. They then made a list of all the artists whose creative practice has not been mentioned over the last decade, and asked seven veterans of the Hong Kong art community including Johnson Chang Tsongzung, Lui Chun Kwong, and Kurt Chan (Chan Yuk Keung) to narrate their impressions of these individuals. Several people’s reminiscences about the same person uncover memories that converge and diverge at different points in the interview video. “Each individual is important. Your existence on Earth is hugely significant. There are topics and issues all around you, and the information is fascinating, but how can the information be transformed into art? This process should not be taken lightly…. These seven art professionals not only had interesting stories to tell, the way they expressed their memories in the interviews were even more interesting. Furthermore, there is no right and wrong when it comes to memory, there is no so-called satisfactory mode of expression.” This piece also reminded me of “He was Lost Yesterday and We Found Him Today”—a project resulting from Leung Chi Wo’s frequent collaborations with this wife, Sara Wong. In that series, the artists posed as background figures found in photographs in media reports; the existence of these anonymous figures at one point in time is activated and verified by the photos. Though this type of memory is entirely bereft of the personal, their very unfamiliarity evinces universal concern.

Word games are another important dimension of Leung’s work. The artist once took the entry regulations of the 2005 Hong Kong Biennial and scrambled them into an unintelligible language. He also deconstructed the lease terms of the Hong Kong Cultural Center. The artist rearranged the punctuation within the document, reformatted the contents as a poetry anthology, and published it as a book. At the end of May, 2015, Leung will perform some of these “poems” at the exhibition. The artist has also done a series of works revolving around “names”, including “My Name is Victoria”—a series of 40 interviews with women named Victoria, who talk about why they are called “Victoria”, and “I don’t like my name”—the artist compiled a binder full of printed pages of Google search results for the phrase, “I don’t like my name”. While Leung’s newly exhibited piece “Asia’s World City” could practically be an opinion poll. The artist collected hundreds of email responses to what they wished for “Asia’s World City”, after selecting 12 responses, he reversed their meaning, printed the reversed responses on to huge posters to be hung in Hong Kong’s public spaces until they were confiscated by the city. Interestingly enough, the only poster that was not confiscated is now hanging outside of OCAT Shenzhen, it is entitled, “Hong Kong: Asia’s World City – No jealousy free zones.”

“Asia’s World City” can be seen as an extension of Leung’s many years of thought on urban spaces. Since 1999, Leung and Sara Wong have been working on their longest collaboration to date. The series entitled “City Cookie” is conceptually simple; they photograph the sky at urban intersections, and make cookie moulds based on the shape of the sky in the photos. Cookie moulds of the sky in New York, Toronto, Shanghai, Venice, and Hong Kong are presented in the exhibition or used to bake actual cookies. These are then sold to viewers or bartered for objects of equal value. Leung made a video for “City of Cookie Shanghai”, recording Sara Wong gradually munching through one cookie after another. “City Cookie” was first shown at Queens Museum. Leung reminisces, “At the time, the curator said something really amazing: ‘This is a grand insignificance’.”

Here, the nearly ubiquitous opinion that Hong Kong artists are “delicate, approaching big issues from small details” begins to show faint traces in Leung’s work. However, we should avoid classifying or stereotyping the artist, especially because Leung’s frequent participation in international artist in residency programs has given his creative practice free reign to slip out of Hong Kong’s context, and into others.

For the curator Carol Yinghua Lu, one of the goals of this “survey exhibition” is to define the show as the first retrospective of Leung’s work while the artist is at the mid-point of his career. As this is Leung’s first exhibition in Mainland China, Lu’s other goal is to promote dialogue and understanding between the art communities of Hong Kong and Shenzhen. Leung’s response to this vision of artistic exchange between the Mainland and Hong Kong as follows, “It takes more than one artist to create artistic exchange. We need to do it as a community, with a number of initiatives. It could even involve tourism—it doesn’t have to be about art. But once an artist’s piece has been expressed, we should give the audience an environment for feedback, so that people who are interested in giving it can do so. This condition is rather important.” Perhaps such an environment is not yet mature, as reflected by Customs holding back a portion of the art works.

The navigation bar on Leung’s personal website (leungchiwo.com) also features a row of round buttons. Clicking on them takes us to more works and documents. This is when the viewer begins mimicking Leung’s actions, excavating and researching, attempting to parse out the different relationships between these works on the internet as I have done for this article. Leung has little regard for artist as an identity; he has more faith in the individual: “Artists are useless, they can’t solve any real social issues. Artists contribute by directing the attention of others towards issues…. When critiquing the merit of an art work, we should consider the thought process that led up to it, and whether the artist has found a way to express those thoughts…. It’s important to do the things that you as an individual find reasonable, and give a spatial relationship to that rationality.”

Leung Chi Wo

Born in Hong Kong in 1968, Leung Chi Wo obtained his Masters oin Fine Arts from the Chinese University of Hong Kong and co-founded Para/Site in 1996. Leung studied the culture of photography at Centro di Ricera e Archiviazione della Fotografia in Italy, studying under Paolo Gioli and Guido Guidi. He has participated in artist residencies in the United States, Australia, Japan and other countries, and his works have been shown in solo and group exhibitions around the world. He currently resides in Hong Kong, and teaches as an Assistant Professor in the School of Creative Media at the City University of Hong Kong.

亚洲国际都会-唯一一幅未被香港城管没收的横幅悬挂在OCAT深圳馆外

the only one banner of “Asia’s World City” outside of OCAT Shenzhen that’s not seized by government

新界大围1-528x523.jpg)