On November 9, while clearing my desk and girding myself for the list of shows to see in Shanghai, “the City of Magic, the City of Demons” (1), I listened to live commentary about the American presidential elections on Swedish radio. I understood how underlying Trump’s shocking, provocative utterances was a political program he extolled, and I began to feel for the first time the ferociousness of the people shaking up the political establishment—a sentiment originating in the ferocity of people’s blind desire for change. Then, Trump became president-elect.

I feel that the exhibitions on that day and following it are worth looking at with a sense of doubt about the establishment and with a questioning attitude. Here are my observations.

(1) Just as New York is called the “Big Apple”, Shanghai is called the “City of Magic and/or Demons” in Chinese (Modu; or Mato, after the 1924 novel by the Japanese writer Shofu Muramatsu).

Aike-Dell’arco (Building 6, 2555 Longteng Avenue, Xuhui district, Shanghai, China), Nov 9–Dec 10, 2016

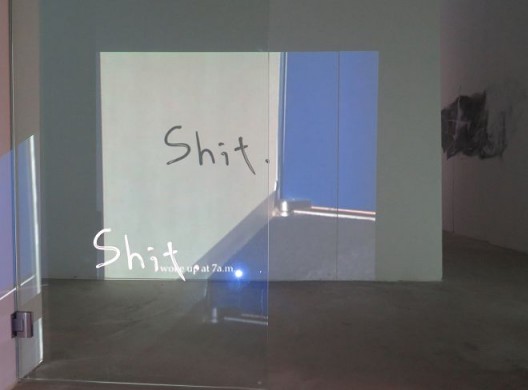

On the newly renovated glass door at Aike Gallery, Lee Kit has left four letters: S-H-I-T. Behind the glass door, visitors are led into a narrow passageway, the walls on both sides of which have ink-smear graffiti on them; the light from a projector shines right into one’s eyes. Avoiding the light, you turn to see a small painting hung on the wall where the light is projected. In it are two figures sitting behind a table, with their features and bearing blurred; beneath them is the word “Idiot”.

“Shit” and “Idiot” seemed to sum up the state of the world on November 9. Practically as Lee Kit’s solo exhibition opened, the American election results were announced. Most people were still digesting the fact and considering what four years of a Trump presidency will bring for the world and for everyone’s daily lives, and yet Lee Kit’s scribbles seemed like a premonition. “I’ve been doing some thinking over these last few days. It’s normal. We have all been thinking about something the past few days. Like the way our faces are oily in the morning. It’s similar to a catastrophe.” Lee Kit wrote what he thought with tiny lettering in an obscure spot on the entrance wall. As is true for his entire oeuvre, one must take time to absorb his work; one is then led willy-nilly into the circumstances of the work: the suitcase in the corner, the window shades that are half-open, half-closed; turning your head in the dim light, you meet own gaze in the mirror.

The obsession with the self is the most intense representation of the modern split personality. In an age when social networks take the place of psychological analyses, you show off on WeChat Moments and earn X number of “likes”, and your immediate satisfaction and approval are quantified ever faster—and ever emptier. Lee Kit’s art acts like the operation of the “dash”—connecting as well as opposing, presenting what is similar and what is different, building fuzzy connections.

One light is projected on a painting on a cardboard box for Nivea hand lotion. The subtle relationships between the works come from their being linked together, like joining the dots, thanks to viewers moving between them in the space; from dot to line—and, thanks to the light—from line to plane. Between the glossy, unctuous sensation on our faces (“Like the way our faces are oily in the morning”) and the rejection of righteousness and idealism as worthless (the American election) there is quite a distance, at least in the scale that disasters are measured—so what can artists do in this field?

I faintly remember Lee Kit telling me he would never live in Beijing. The reason? He can never forget the horrors of the past. Resistance may be quiet, but indignation multiplies. The worst has already happened; Lee Kit’s work, however, speaks softly.

李杰 “过去几天,我一直在想一些事情。”,展览现场 (感谢艾可画廊提供配图) / Lee Kit, “I’ve been doing some thinking over these last few days”, exhibition view. Courtesy AIike Dellarco.

李杰 “过去几天,我一直在想一些事情。”,展览现场 (感谢艾可画廊提供配图) / Lee Kit, “I’ve been doing some thinking over these last few days”, exhibition view. Courtesy AIike Dellarco.

李杰 “过去几天,我一直在想一些事情。”,展览现场 (感谢艾可画廊提供配图) / Lee Kit, “I’ve been doing some thinking over these last few days”, exhibition view. Courtesy AIike Dellarco.

李杰 “过去几天,我一直在想一些事情。”,展览现场 (感谢艾可画廊提供配图) / Lee Kit, “I’ve been doing some thinking over these last few days”, exhibition view. Courtesy AIike Dellarco.

Antenna Space (202,Building 17,No.50 Moganshan Rd.Shanghai), Nov 9, 2016–Jan 10, 2017

According to Greek mythology, a “Chimera” is a hybrid, fire-breathing creature; Chimera also happens to be a type of 3D modelling software developed by the University of California, San Francisco. While scientists establish analytical logic based on facts, artists can enable science to break out of the protective vacuum of the laboratory, affording poetic imagination of the shapes under the microscope.

For Nadim Abbas’s first solo exhibition at Antenna Space, the space has been divided into a laboratory and display area. “Human Rhinovirus 14” (2016) shows various facets of the virus as images which are projected onto spheres hovering in the air. Accompanied by the noise of whirring blowers, viewers have entered a fictional world populated by viruses. This is first of all a very odd “human invasion” by an artist into the world of viruses; who knew there could be a certain romance and sentimentality about viruses blown up to thousands of times their actual size? The images projected on the spheres have something of the freehand suggestion of ink painting, and are wafted in the air by the blowers. The several spheres floating together prompt viewers to astronomical imaginings and, at the same time and in spite of themselves, to imagine the destructive act of turning the blowers off. Thus, a sense of the unknown and perplexity are what is intriguing about the work. If this sense is still connected to the human, then the “supermoon” talked about recently seems to offer an example closer to home; of course, the roar of the blowers in the gallery space also pulls us back to Mother Earth.

Nadim Abbas’ work cuts across worlds. Ultimately, he is an artist who imagines and adds to science. “Chamber 667” (2016) goes so far as to preserve the setting for a “super-scientist”, their hands shielded in gloves that reach into and out from a sealed tank; the models scattered about inside these tanks echo the original meaning of modelling. From the rolls of toilet paper in their sealed chamber (#668), we might imagine a physiological reason for the scientist having rushed from the scene. Just like the “blancmange” wallpaper installation in this exhibition, in which a photo of the famous dessert with a fly on it hangs against wallpaper printed with a host of mini-blancmanges, Abbas’ game originates in wordplay that becomes the atmosphere of his science fiction scenography; it is an atmosphere of lunchboxes and snacks left around for too long inside an otaku’s bedroom laden with the artist’s identity and background. Whatever is left behind in translation after playing with English words might be a most effective way of reinterpreting the artist and his work.

With art that takes science as its point of departure, the first problem encountered is the way to view or deal with the world. Science demands accuracy, while art lends a rich and chaotic element. For the philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend, the fuzziness and nonsense of poets, painters, and musicians served to dissolve the rigidity and objectivity of scientists (in his own words: “The only principle that does not inhibit progress is: anything goes.”). Abbas’s viruses celebrate the want of meaning.

Leo Xu Projects (Lane 49, Building 3, Fuxing Xi Road, Xuhui District, Shanghai 200031, China), Nov 9, 2016–Jan 15, 2017

In the ground floor space at Leo Xu Projects is a yellow-green carpet on which lies the sole of a shoe (the artist’s). Diagonally opposite is a roll of partly tangled tape hanging from the ceiling, and rubber bands (collected by Nina Canell). Extending a straight line from the rubber band to the corner of the wall opposite, it will hit upon a bronze pipe that snugly fits the shape of the wall corner. Right where the corner turns, the pipe is replaced by a neon light; the rope connected to the pipe stretches out into the next room, where in the opposite corner is a “device” (the artist calls this a sleeping device) emitting a noise filling the room. Occasionally, a timer that announces the time will break up the noise, instigating an instant of silence. If this brief moment of tranquillity has something to do with sleeping, then Canell’s work up to this point recalls for me that moment of awaking from sleep, lying on the sofa, the remote having dropped from one’s hand to the floor, and who knows when the television programs had finished with the night-time weather forecasts and the screen reverted to its war-of-the-ants static, humming that tidal-sounding sound. The watch says it’s still too early to get up, and it’s too late to go back to work. Resentfully, you turn off the TV, wash, and sleep.

The ability to place seemingly unconnected objects together and then use basic physical elements—rubber bands, semi-conductors, welded parts, wiring, noise—to connect them: all this meticulously presents the combination of scientific logic and a dreamer’s illogic with which Canell’s work invests everyday objects and readymades.

Cool, simple exteriors and intriguing work titles (“Jelly-filled vowel”, “Brief Syllable (heavy)” hint at a relationship with sound and perception. In the sculpture in the second floor space, which is made of high-pressure optical cables sectioned off and sealed inside glass before being placed on top of a concrete pedestal— Canell touches on a complex relation [of the actual object] from Berlin to Shanghai, from Pudong to Puxi, from the narrow windows of the gallery to the concrete pedestal base [they relate in a certain ratio].

The title of the exhibition “Reflexology” of course first makes one think of foot massages; it is also the principle of conditioned response, as in Pavlov’s dog. Canell’s work ponders exchange and misunderstanding, a proposition succinctly represented using scientific theories annotated with art. Art creates connections between disciplines, overriding national and regional boundaries, and fosters the mutual enjoyment of artists of different generations. This, in part, is the theme for “Mirrored” which is to be shown in the Nordic pavilion at the Venice Biennale next year, curated by the Moderna Museet. Nina Canell will be the youngest of six participating artists.

尼娜·卡内尔,《最柔软的角落》,铜、霓虹灯、氖变压器、电缆,尺⼨可变(感谢LEO XU PROJECTS提供配图),2016 / Nina Canell, “Softest Corner”, copper, neon, neon transfer, cable, Dimensions variable, 2016. Courtesy Leo Xu Projects.

尼娜·卡内尔,“反射⽳”,展览现场(感谢LEO XU PROJECTS提供配图) / Nina Canell, “Reflexology”, installation view. Courtesy Leo Xu Porjects.

尼娜·卡内尔,《简单音节(重)》,地下电缆、亚克?、混凝?,16.5 x 16.5 x 111 cm(感谢LEO XU PROJECTS提供配图) / Nina Canell, “Brief Syllable (Heavy)”, subterranean electricity cable, acrylic,concrete, 16.5 x 16.5 x 111 cm, 2016. Courtesy Leo Xu Projects.

尼娜·卡内尔,《自由空间通路遗失》,高温、氧化指纹、铜管,84.5 x 2.5 x 117 cm,2016 (感谢LEO XU PROJECTS提供配图) / Nina Canell, “Free-space Path Loss Heat”, oxidized fingerprints, copper, 84.5 x 2.5 x 117 cm, 2016. Courtesy Leo Xu Projects.

尼娜·卡内尔,《双翼馆》,调频发射器、调频电台接收器、蠓虫活动磁场静电录音,尺⼨可变(与Robin Watkins共同创作),2014 (感谢LEO XU PROJECTS提供配图) / Nina Canell, “Two-Winged Pavilion”, FM transmitter, FM radio receiver, electrostatic field recordings of midges and the magnetosphere, Dimensions variable (Produced with Robin Watkins), 2014. Courtesy Leo Xu Projects.

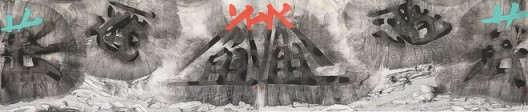

“Gu Wenda: Journey to the West”

M21 Museum (No,1929 Shibo Dadao, Pudong, Shanghai), Nov 9, 2016–Feb 15, 2017

In a thirty-year retrospective of an important pioneer in the history of contemporary art in China, the word “big” is unavoidable. Some 25,000 gold and red lanterns cover the exterior structure of the museum; inside, several thousand bricks the size of those furnishing the Han dynasty wall but made of human hair stack up to form part of a “Great Wall”, and, for a recent piece in Shenzhen that is recalled here, Gu invited 1,500 children to write in calligraphy Confucius’ The Classic of Filial Piety onto silk cloth using pigment made from algae. Sections of this work hang in the middle atrium from a ceiling dozens of meters high; with them extends a deep sense of insecurity, the form of the classic “Big Character Poster” having had its content replaced. There is that collectivist spirit, almost like the opening ceremony of the Olympics, when many people single-mindedly focus their energies. Beyond the sense of ritual, what comes through, with the help of art, is the official line about promoting culture and the will to power.

In this exhibition, one sees the avant-garde works Gu Wenda had created in the 1980s by fusing music, literature, and ink art, with a meticulousness and spectacle that transcend the times. And there is the subversive recombination and recreation of Chinese writing, the Stele series about the exchange and export of culture, human hair, genes, alchemy—Chinese symbols sweeping all on the path to “conquer the West”. This return to Gu’s hometown feels unfamiliar now, as though the product of a different age. With his illegible writing and opaque hair that cannot be seen through, culture is translated back again in this homecoming of the traveller.