Singapore Art Museum (71 Bras Basah Road), July 31–Oct 22, 2014

Often, when brash young artists come to the realization that the sense of sight is accorded special significance in art, they are moved to challenge this hierarchy by choosing to privilege, say, the Dionysian sensuality of touch and taste over the penetrating coldness of Apollonian vision. The benefits of substituting one hierarchy for another aside, however, these efforts often miss the elephant in the room—that this scheme of five senses is about as hoary and valid as the theory of phlogiston to explain combustion, or the pre-modern medical theory of humors. Swallowing it uncritically and without examination would seem to pose risks analogous to having a “chirurgeon” come round to bleed you for a cough—or at least risks similar to those of unquestioningly acceding to the supremacy of the eye.

In this regard, the latest show by the Singapore Art Museum, “Sensorium 360°”, comes as welcome respite. Among other less familiar senses, the show also touches on proprioception, kinaesthesia, and chronoception, questioning the dominance of vision in art while also expanding the sensory field beyond the traditional five; its title suggests that establishing a definite count and hierarchy is besides the point. There being relatively little by way of established aesthetic traditions concerning these senses, the exhibition’s ambition seems to be to rise to such a challenge, hopefully breaking new ground in the process.

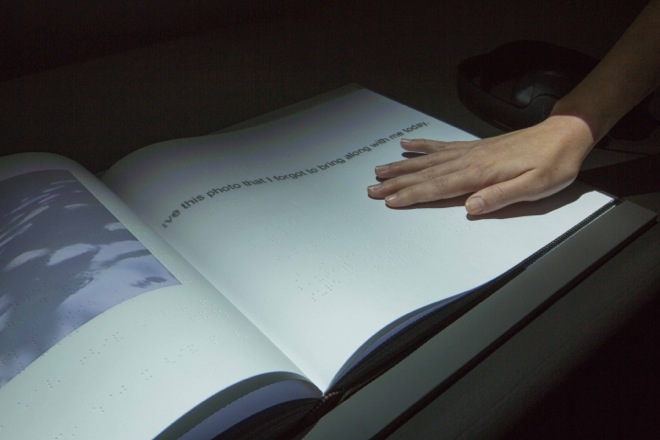

Alecia Neo’s “Unseen: Touch Field” bills itself as a work which dislodged sight in favor of touch, based on Neo’s work with the visually impaired. Oddly enough, the work is relatively brightly lit, allowing us to see dark panels of Braille-like imagery, drawn from “tactile drawings” by visually impaired participants of commonplace scenes in their surroundings. In an exhibition dedicated to fully exploring the senses, though, it seems markedly odd to frame one sense—touch—in terms of the absence of another, by leveraging those who lack (or have severely impaired) vision, somehow echoing some sort of “sighted-man’s burden.”

In a somewhat similar vein, Lavender Chang’s “Unconsciousness: Consciousness”, while touted as a work centered on chronoception (or the perception of time), consists of a series of five prints. While each print is built on long exposures of sleeping figures in bed, the sense of time here is one of represented time, translated into a still image—much as the pain and duration in Melati Suryodarmo’s “Alé Lino” can only be experienced (unless you were present on the opening night) as documentary traces.

Chang’s actual images, while undeniably ravishing—elegiac contortions of some noctilucent fever-dream—engage with our sense of time as still images tend to, through our capacity to imagine what has transpired in its making and the passage of time experienced (or not, since they are sleeping) by the half-glimpsed figures in each image.

Lavender Chang, “Unconsciousness – Consciousness”, 2011-2013. Image courtesy of Singapore Art Museum

On the other hand, Eugene Soh’s “The Overview Installation” offers the tantalizing premise (through augmented reality) of literally removing ourselves from our familiar binocular perspective to instead approximate the point of view of, say, a lizard or another participant while navigating a simple maze. While the disorientation of ocular dislocation is as dizzying as it sounds, there is a lingering sense that the work as a whole feels more like a technical demonstrator, some proof-of-concept prior to a developed work.

As opposed to a single note of sensation, Mark Wong’s “Memory Rifts” proffers a technically simpler, yet aesthetically and sensually efficacious experience. By simply dispersing a nine-instrument composition across nine points within the museum, Wong obliges us to physically traverse the space in order to hear parts of a piece of music that cannot be heard as a whole at any one point in space. In other words, audition is keyed to our kinaesthetic, proprioceptive, equilibrioceptive (sense of balance) and—if your balance suffers when lost in music and you fall down the stairs—nociceptive (related to pain) capacities. In truth, it is almost beside the point simply to enumerate the exact senses that become enmeshed with this active sense of audition—of listening, rather than hearing.

Goldie Poblador’s “May Puno sa Dibdib ng Kamatayan (There is a tree in the heart of death)” also expresses this bridge between the senses. Poblador’s stated objective is the exploration of synaesthesia, specifically in the confusion or co-mingling of sound and scent, as senses perceived to have a greater capacity to stir our memories and evoke emotional responses.

The work itself revolves around the idea of translating musical composition to that of scent, with the visitor enjoined to compose their own arrangements of scents, with reference to vials of smells that Poblador associates with pieces of music in an adjoining room. A consequence of playing amateur parfumier (the “nose”), though, is that one has to repeatedly bend down to open and sample bottles of various scents. It is a repetition which could recall some sense of either meditative discipline or assembly-line drudgery, invoking also the senses of one’s own bodily positions and movements; even as the boundary between scent and sound is deliberately crossed, other boundaries blur and shift as well.

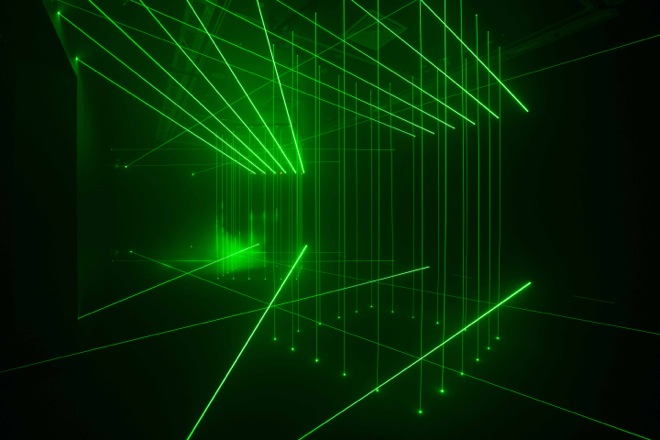

Li Hui’s cages of green lasers flicker in and out, forming a shifting pattern of barriers and boundaries which, though visually imposing, are about as physically substantial as one would expect light to be—inviting anything from the classic miming routine of the invisible box, or imagining yourself in Mission Impossible. Levity aside, Li’s “Cage” relies on the relationship between our visual and spatial senses of our surroundings, flowing rapidly between congruence and disagreement; Li’s work also alludes to the notion that the boundaries that we determine are largely reliant on our own perceptions.

Similarly, in proposing some grand tour of the human sensorium, the show as a whole, though phrased in terms of specific senses, exhibits this same uncertainty of boundaries—those works which were shoehorned too forcefully into a given sensory category betray this instability. Our senses, it seems, are not as neatly demarcated as the language we rely upon to describe them; they flow and shift and bleed over into one another, as anyone who’s held their nose to choke down some bitter medicine can readily attest.

Christina Poblador, “May Puno sa Dibdib ng Kamatayan (There is a tree in the heart of death)”, 2014. Image courtesy of Singapore Art Museum