“Medium at Large”: group exhibition

Singapore Art Museum (71 Bras Basah Road, Singapore) Apr 24, 2014–Apr 1, 2015

“The medium is the message.” It has been fifty years since Marshall McLuhan introduced that phrase to the world—long enough ago, perhaps, for it to be little more than a pithy catchphrase for many. The details of his theories notwithstanding, artists have long sought to mine the possibilities offered by new technological developments.The specifics may vary—whether coding an image of the galaxy into a mouse’s ear or stretching canvas over a wooden frame—but the tendency remains, and in each instance, the medium of transmission presents its own set of implications and pitfalls. Chief among them might be to treat the medium as a subsidiary player, no more than a means of conveying information—reducing the medium to massage—soothing, relaxing, and otherwise unremarked-upon.

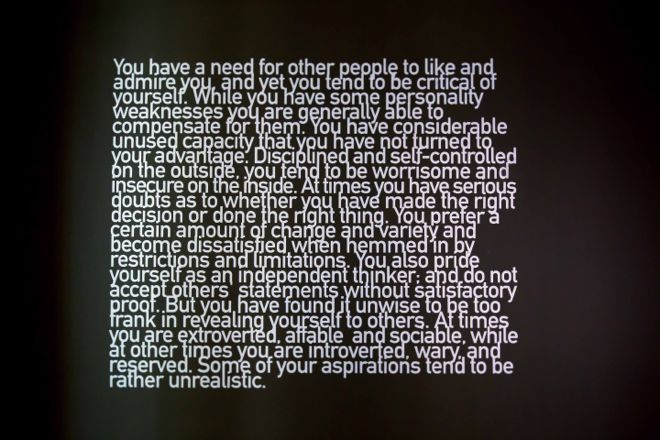

With this in mind, it is refreshing that a visitor to “Medium at Large” at the Singapore Art Museum (SAM) might first encounter Heman Chong’s “The Forer Effect”. It is a text-based work—a medium not known for easy acceptance by audiences primed to expect mimetic craftsmanship, some sign or gesture of personal investment and expression, or at least a sensory spectacle. The text of the piece, drawn from Bertram Forer’s 1948 experiment, comforts and uplifts—unremarkably anodyne statements that were nonetheless judged by participants to be accurate, individually tailored assessments of their own personalities: statements like, “you have a need for other people to like and admire you, and yet you tend to be critical of yourself,” or, “at times, you are extroverted, affable and sociable, while at other times you are introverted, wary, and reserved.” With its busy, crowded layout, it is a challenge on multiple registers, perhaps in order to have one feeling discomfited and off-centered at the start of the show.

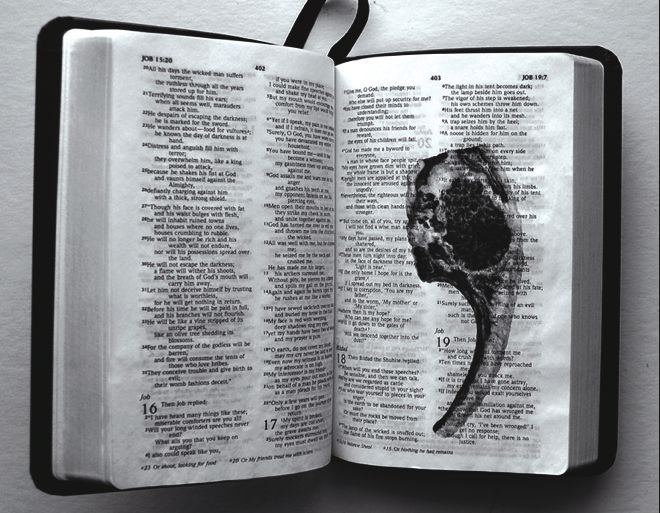

Rento Orara’s “Bookwork: NIV Compact Thinline Bible (page 403),” as the precisely detailed title might suggest, presents another medium with a history of controversy and provocation—the readymade, a form which might be held to have pre-empted McLuhan, in the sense of evacuating content while shining a light on context and supposed infrastructure, resulting in a storm which has yet to fully abate. However, Orara takes a rather different approach to the readymade, blending it with a more traditional, approachable field: skilled draughtsmanship.The Bible, open at the Book of Job, features a lamb chop lovingly rendered in ballpoint pen, suggesting a viscerality to be read within the context of the text’s symbolic language: one of violent despair, at the depths of Job’s trials, with images of skin gnawed at and limbs devoured.

Neither fully a readymade nor a drawing, the work touches on one of the key topics addressed in the show—the habit, in contemporary art, of blurring and crossing the increasingly unstable boundaries between different media. Are these hybrids and chimeras simply the sum of some set of qualities culled from their parent media, or does something more come into effect? What becomes of prescriptive systems of media classification as fluid, shape-shifting approaches become ever more commonplace? Perhaps a shift to the descriptive, moving medium from definitive pronouncement to site of contention, as perspectives are re-framed and influences, similarities and associations are debated. We might speak of strains of performativity and draughtsmanship within a given work, rather than attempting to fit it within categorical boundaries: something akin to the shift from Linnaean kingdoms to cladistics and molecular phylogenetics, which rely on genetic markers, rather than morphological similarities, to group species together. If biologists can discover that hyraxes, sea cows and elephants – animals that hardly look alike – are closely related, maybe there are analogous possibilities in store for art.

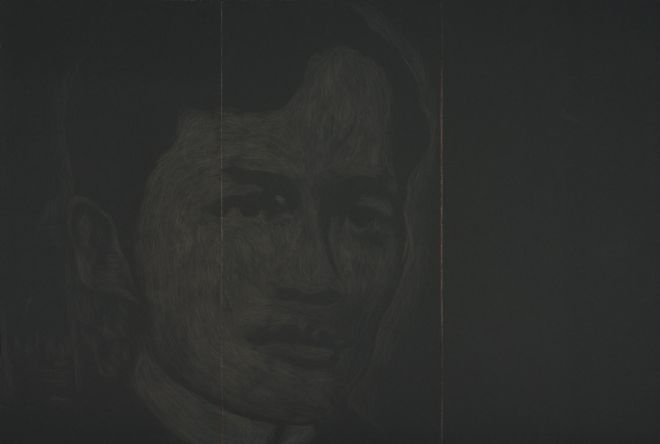

On the subject of hybridity and boundary-crossing, Alvin Zafra’s “Pepe and Marcial Bonifacio” appear at first glance to simply be drawings of some kind—glittering flecks of brass on a roughly textured grey ground. However, reading the accompanying label supplies the context: the men depicted were prominent figures of Filippino political history, both of whom met their ends at the barrel of a gun; their portraits were rendered by grinding a bullet on sandpaper. While the symbolism of the material is evocative—of history, violence and nationalism—it only emerges once information external to the artwork is supplied.

While this might ordinarily be seen as something of a weakness, perhaps there is another perspective from which to view this. If we were to consider the museum, the exhibition, and the systems which underlie them as a medium in and of itself—like the drawings of Nadiah Bamadhaj taking, in effect, the entire wall as their ground—then hard and fast divisions between works and their accompanying text might no longer be so ironclad: a different sort of boundary-crossing.

It doesn’t seem as much of a stretch when one considers the place of documentation in the case of ephemeral and performative works, as seen with Chen Sai Hua Kuan’s “Space Drawing 5” and Melati Suryodamo’s “Exergie–Butter Dance (Sao Paolo).” In each instance, it is only the documents that remain in the space with us, by way of photography and videography. However, within a frenetically mediated, mediatised world in which electronic representations are ceaselessly copied and remixed across globe-spanning networks, can the status of the document really be disparaged as having descended from a truer original?

As far as these works are concerned, however, there is also another question: that of their reclamation or reappropriation by systems of commodity and interment within a canon. After all, the ephemerality of performance can be traced at least in part to a desire to produce artworks that would resist the twin pressures of commerce and the institutional canon, by the act of simply refusing to produce persistent, stable objects. In addition to the infrastructural functions of trading and sacralisation, performance’s turn to transience sidesteps galleries and museums as media in themselves – media through which artists and the public communicate. While the ready adoption of performance documentation by galleries and museums could be viewed as performance’s resigned return to the fold, the critic Philip Auslander has a different perspective: that these recordings are “no longer documents of ephemeral performances, but often consitute virtual performances in themselves.”

These institutional instinct to inter and canonise are referenced (or perhaps lampooned) by Gerardo Tan’s “thisisthatisthis” and “thatisthisisthat”, confusingly named works in which dust from notable paintings (dating to 1895 and c. 1740s respectively) is painstakingly redeployed to make artworks in their own right. “thisisthatisthis”, in particular, does so with an additional touch of panache, framing a tiny black square of dust, rich with provenance, within an oversized gilt frame.

Also upending the conventional relationship between artist and institution is Alan Oei’s “The End of History,” an installation which emerged from an episode of artistic imposture in which a mid-twentieth-century Singaporean painter was supposedly rediscovered, complete with paintings and artifacts. The fiction, scripted by Oei in collaboration with Kaylene Tan, a theater practitioner, constituted a performative play on authenticity, historicity, and the function of painting, ranging across the institutions of artistic infrastructure and the public.

Taking a more explicitly relational tack (and one characterized by earnestness, or at least an attempt to elicit earnestness) is Song-Ming Ang’s “You and I”, a three-year project in which the artist extended an invitation for people to write to him, sharing something personal, to which he would respond with a tailored mix of songs drawn from his personal collection of music. Both sides of these intimate exchanges are on display, inviting some comparative speculation as to correlations between the content of the public’s letters and the resultant selection of songs. However, the content of the work aside, there is also the matter of the work’s medium—does it lie in the explicitly sensory artifacts of hand-written letters and CD-borne MP3 files? The interpersonal relationships between artist and participant—and maybe even the postal systems linking them?

Given the growing tendency for artists to blend different media, and otherwise break or bend the distinctions between them, the exhibition as a whole evinces a sense of relative stability and solidity, with relatively little by way of challenging, novel media. Of course, a show with such scope could hardly have the bleeding edge of experimentation as its sole focus; but then, perhaps skewing to relative stability is a feature deeply embedded in the medium of the museum itself.