“Diamond Leaves — Brilliant Artist Books from Around the World” (group exhibition)

Central Academy of Fine Arts Museum (No.8 Huajiadi Nan St., Chaoyang District, Beijing). Sep 18 – Dec 18, 2012 (closing date extended)

In today’s world of virtual communication and visual explosion, this could be a purely metaphysical question. In a more profound sense, books could be an indication of the times, or else as Pierre Bourdieu said, they signify “symbolic power” since books and reading had been the sole privilege of a society’s elite for a long time in history. With limits imposed by print technology and education, the ties between books and texts were extremely intimate, so much so that having a text would seem to define inarguably what a book is. Yet in CAFAM’s exhibition “Diamond Leaves – Brilliant Artist Books from Around the World,” we see what else books can be.

Intricate curation aside, what makes this show special is the gamut of ideas about art and cultural history it inspires in the viewer through this non-mainstream medium of handmade artists’ books. The particular format of an artist’s handmade book originates in the illuminated books of the 18th century Romantic artist and poet, William Blake. However, more appeared with the wave of 20th century avant-garde art and culture.

The first question an average viewer might ask is, “What is an ‘artist book’?” Although the curator was reluctant to limit and define this, the ambiguity could easily make “artist books” to be confused with “art books” — the latter being ornate limited-edition books, usually related to literature, which publishers often ask artists to illustrate. In such cases, artists more often illustrate according to the text and rarely have the chance to reflect their own will. This is why the priceless religious manuscripts of the Middle Ages and the later 14th- and 15th-century magnificent volumes like Les très riches heures du Duc de Berry illustrated by the Limbourg Brothers, exquisite as they are, do not qualify as artist books. In other words, “art books” fall under the category of decorative art, whereas “artist books” are pure art.

In this show, artists pushed the boundaries of their imagination within the restrictive size and format of a book. The “book” is conceptualized and linked with film, installation, illustration — even the sense of smell. For instance, materials like cinnamon, wild cherries, and tree bark were used to create the sole edition of Mesopotamia (2010) published by Organik; the pages were covered in yellow plant pigments, which combined with thickly textured effect and giant images of insects recalled a of a Middle Eastern desert. In the display cases, round holes were even created, allowing viewers to take in the fragrance of the spices and be transported to an imaginary Mesopotamia.

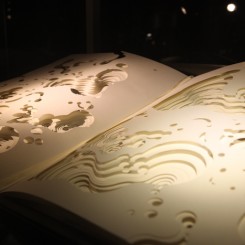

Similar manipulation of the senses and subversion of form was also seen in another work, “Duchamp.” The artist, Robert The, used a razor to “dig” out the shape of an insect from an open book of Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical paintings, and then hung this “insect” on the white wall above the book — which from afar looked very lifelike. To surreally carve an insect out of de Chirico’s surreal images, and then calling the whole piece “Duchamp” is just marvelous — a dream within a dream, decadence upon decadence. This interest in art history and the art world has often served as a theme for artists, as seen in Bongoût’s wire-mesh work “If,” where he uses wire mesh to recreate the representative work of every artist he has ever worked with. Similarly, another artist, Chuck Close, and a poet, Bob Holman, collaborated in a photo album, combining modern art and high-resolution photographs of music stars, as well as Chuck Close himself and Cindy Sherman.

Although there is no lack of artist books displaying breathtaking works of labor and intricacy — like Candice Hick’s “String Theory,” (2011) where the artist used her impressive needle skills to sew an entire notebook filled with lively threaded words on cloth — other works like Ken Campbell’s “Ten Years of Uzbekistan” (1994) impact the viewer more deeply. The Russian Constructivist artist Alexander Rodchenko designed the original copy of this book for Stalin, but by the time the project was over, many of the individuals mentioned had been purged. Naturally the edition was destroyed, but Stalin ordered the artist to preserve a copy, and so Rodchenko blacked out the faces of those killed with ink. Later this book was purchased at an auction by a friend of Ken Campbell and reprinted. We have no way of knowing the identities of these people as their faces have been covered by ink — as though they have fallen forever into the black hole of history, leaving the viewer with a lingering sense of depression and horror.

As a “footnote” to this exhibition, some ancient Chinese and European texts are on display. There is the Buddhāvatamsaka Mahāvaipulya Sutra from the Ming Dynasty, along with ancient illustrated religious scrolls such as the Sacrarum Caeremoniarum sive Rituum Ecclesiasticorum, published as early as 1582. However, this “footnote” show is not closely related to the artist books, and merely displays works with the juxtaposition of image and text. What is most interesting here is the full range of traditional book-binding tools displayed. At the opening ceremony, the curators invited craft artists like Wang Wenda to put together a book with these tools. This certainly presented lively way of understanding the craft and created a workshop-like atmosphere for the audience, where we can truly experience the allure of books. We can contemplate what books are, how they have brought about civilization, and how they allow us to perceive beauty.