Guo Zhen is an artist who currently lives in New York’s Washington Heights, where she paints and teaches art. In 1982, Guo Zhen graduated from the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts in Hangzhou, one of China’s most prestigious art colleges. After graduation, she was asked to remain at the academy as an instructor in recognition of her excellence as a student. Guo Zhen emigrated from China to the US in 1986. Her art has been widely exhibited in cities throughout the US, including San Francisco, Chicago, Washington DC, San Diego, Los Angeles and New York. The conversation published here focuses on Guo Zhen’s time as an art student in China during the late 1970s and early 1980s and gives a detailed personal account of some of the changes and conflicts that took place within the Zhejiang Academy following from the adoption of Deng Xiaoping’s policy of opening-up and reform in December 1978.

Paul Gladston: You were an art student in China during the 1970s and 1980s. Where did you study and what were you taught?

Guo Zhen: After the end of the Cultural Revolution, I passed the National College Entrance Examination. I went to Hangzhou in 1978 to study in the Chinese Painting Department of Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now known as the China Academy of Fine Art). We were mostly taught traditional techniques, such as sketching, line drawing, figure drawing, traditional Chinese landscape painting, flower painting, meticulous figure painting, calligraphy, and so on. In the first year of college, everything was taught traditionally. During the Cultural Revolution, formal learning had pretty much come to a stop and all kinds of institutional systems had been broken. At the school they wanted to return to normal again, so we started with Western style three-dimensional geometric plaster drawing. Later, we did life drawing and we practiced by copying traditional Chinese paintings and Chinese calligraphy. We also went to the countryside to study the farmers’ and workers’ lives and the landscapes in which they worked. Usually one teacher would lead a class of thirteen to fourteen students. Once each year, we stayed somewhere outside of the school for as long as a month at a time. During these field trips we were mostly studying by ourselves and doing a lot of quick drawings using pencil or ink and watercolors. When we came back to school, we would pin up some of the drawings in the classrooms and hallways to show how much each student had learned, and the teachers would give a grade, such as 5, 4 or 3. The highest score was 5+. Later, in the “Creative Art Works Class,” we would use the experience of the fieldwork to create paintings. Some of China’s best-known painters often came to our classes to demonstrate their techniques. These artists included Lu Yanshao, Chen Shifa, Lu Yifei, Fang Zengxian. They were all demonstrating traditional techniques.

PG: What sort of ideas were taught and discussed?

GZ: I think, at that time, the main idea of teaching at the school was to train the students to have good realistic painting techniques, to learn the techniques of the ancient artists, and to learn how to use those techniques to create new art works which could represent the public and the Communist Party. I remember a funny story which shows the way people felt at that time. One of my artworks was criticized by one of the most respected teachers, the head of the Chinese Painting Department at that time. During the summer vacation of 1979, I went to countryside and did some drawings. From those drawings, I chose one piece to paint and enlarge. This painting included a farmer’s wife breastfeeding a little baby in her backyard. One of her breasts was showing. I was trying to do something a little different, and that was considered bold at that time. On the lower side of the painting, there was a hen with a few chicks which were looking for food on the ground. My idea of this painting was simply to express the requirement of nature that mothers care for their children. However, in one of the full department meetings—in front of all the teachers and students—the Department Head criticized this painting, saying that it encouraged people to have more babies in opposition to the government policy of one child for one couple. When I heard that, I was very nervous, because this single comment could damage or destroy my career at the school. If this had occurred during the Cultural Revolution, I really would have been in big trouble. I stood up and argued back that in the new age, the school should allow new ideas and that art should be free from politics. This behavior was really out of character for me, but I was so involved in things at the time that I couldn’t help having that reaction.

In Chinese Painting classes, we first had to learn how to make the ink, and what the sources of colors are. Some colors are made from plants and some are made from stone or minerals. The colors made from plants are clear and those made from stones are opaque. These are very basic techniques. Next, we learned to copy old traditional artworks in order to learn the techniques of the masters. We did not have discussions about new art until new influences reached our school in the mid-1980s.

PG: How much exposure did you have to Western ideas, art history and art criticism? And how much exposure did you have to traditional Chinese cultural thought and practice?

GZ: We had Chinese art history and Western art history classes as requirements, but there was not much new information. At the time I started college, there were only a few art newspapers and very little work on art criticism. There was no Western art in museums, only in books and sometimes the newspaper. Art critics became more active after I was out of school and while I was still teaching at the Zhejiang Academy, around 1983 to 1985. Around that time, some new books and magazines from Japan and America arrived in the school library. Some of the older Chinese books from before the Cultural Revolution were also released too. I remember that we were all very excited when this happened, and the school built a new library for these books. However, it turned out that they were not available to everyone, only to teachers and graduate students.

There were, of course, always some students who could find a way to get access to the books. Sometimes, teachers brought books to the classroom for students to see. In the beginning most of the books came to us from Japan. Japanese Artists had a big influence. They were like a breeze of spring wind with colorful fringes: so fresh, so beautiful, and easy to understand. It really opened my eyes. Works by Japanese artists such as Dongshan Kuiyi [Higashiyama Kaii] and Pingshan Yufu [Hirayama Ikuo]—I only remember the Chinese version of their names—were more colorful and decorative than Chinese art at the time. Simple landscapes expressed deep feelings. These paintings changed the way we thought about our own paintings. There was also a big movement for students at the time—you could call it a “reading fever”—which was to read books from the West whenever they could, including poetry by Byron, philosophy by Kant, novels by Victor Hugo and Margaret Mitchell, and plays by Kafka. These writers and others opened my eyes to so many ideas.

During the Cultural Revolution, people were not allowed to think about anything new or controversial. Even knowledge of the facts of life like sexual feelings was forbidden. With the end of the Cultural Revolution and the renewed availability of Western ideas, our minds began to percolate, and then to boil out of control with new ideas. It was very exciting. In 1980 the first American student came to Zhejiang Academy. Most people, including myself, had never had close contact with a foreigner and I’m afraid we stared at her unmercifully, as if she were on display for us. All of the girls copied her hairstyle and clothing. Even the aroma of her coffee made us think about what was out there in the world that we knew nothing about. Although she was not important to my artistic development, others soon came, bringing news about the art world and modernism to China. We were shocked to hear about the art of Andy Warhol and Duchamp, which both startled and inspired us. At the same time, we started to learn about the history and development of impressionism and modern art movements, as well as individual artists such as Rodin, Matisse, Picasso, and Dali. We soon wanted to have our own new art.

Lectures by visiting foreign artists were always filled to overflowing. In the evenings there were often heated discussions about Western vs. Chinese art or modern vs. traditional art. I remember that in classrooms full of students and teachers there were sometimes no seats left, so people had to stand outside in the hallways or look in through the windows. There was one particular teacher of Chinese Painting theory, named Zhang Zuan; he tried to answer all the points, showing how the Chinese tradition was superior to that of Western art. Zheng Shengtian, one of our teachers, was the first person from our school to travel to America for cultural exchange. When he returned from Minnesota, he gave lectures about American Art. He brought many slides of artworks from the New York Metropolitan and other museums. He also talked about the different lifestyle in the US. Even something as ordinary as having toast with butter and a glass of fresh orange juice each morning for breakfast seemed revolutionary. He was so impressed by the American cultural lifestyle, which had so much freedom.

We also liked the American lifestyle: fashionable clothing like flared jeans, music such as John Denver’s “Country Roads” song, and long hair all had a big effect. Sometimes, there were parties with ballroom dancing. The waltz and cha-cha were considered OK, but the tango was thought to be too complex. And the boys and girls were allowed to touch! That never happened to our generation before. You can imagine how exciting that was for me and my twenty-something friends! We were all inspired and wanted to go to America, but sometimes it did not work out so well. When the first class after the Cultural Revolution, which entered college in 1977, prepared for graduation, everyone needed to create a graduation piece. This was really important because graduation from a good school could get you a good job. The government was responsible for distributing jobs, but they did not like you to produce avant-garde work. If you received a poor grade or your work was criticized, you might not be given a job—there was no such thing then as an independent artist making a living in China at that time—and then you could be in serious financial trouble. Your teacher needed to approve the project before you were allowed to continue. This was the continuing influence of tradition on the lives of Chinese artists.

In 1981, it was time for that first class after the Cultural Revolution to create a piece of artwork for graduation. Everyone went wild. Inspired by contact with the West and new ideas, everyone tried to be noticed for his or her own leap into the new art world. One of the students, called Lin Lin, did not graduate. Lin Lin was kicked out of school because he was too experimental for the school authorities. He wore long hair, flared jeans and carried a guitar. His painting was very wild and far too abstract for the judges to deal with. Because his work had been criticized, he could not find a job after he left school and had to live with his parents for a long time. Later, Lin Lin came to America. He was supporting himself and his wife by painting portraits on the street, as many Chinese artists who had recently immigrated to the US did at the time. In 1991, in a well-known and very tragic turn of events, he was shot and killed by a street thug in Times Square in New York.

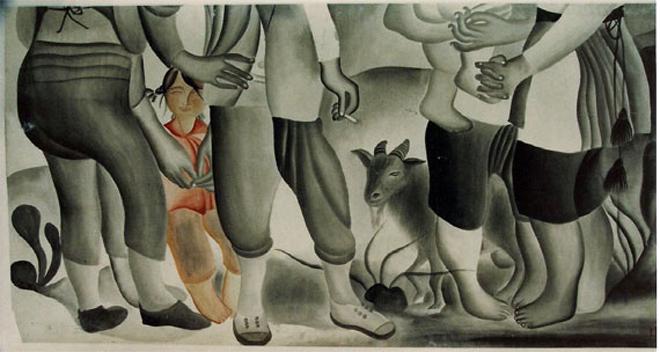

By the second graduation year, 1982—which was my class—the students had quietened down a bit and were less emotional about what they were doing. My first new-style painting was in 1979 or 1980. I remember that it was different because I used opaque colors and a decorative style, influenced by the Japanese paintings we had studied, instead of watercolor or ink like everyone else. The work was probably not so great, but I was so worried that it might not receive a good grade because it was different and because my class work had already been criticized. But I ended up with a good grade and things turned out OK.

At the end of my third year in college, I went to Dunhuang to study the ancient murals. It took two days to get there from Hangzhou, and we stayed over one month. We lived very close to the caves and spent almost all of our time copying the murals for our department. This trip had a big effect on my future paintings, especially the work I created in the late 1980’s. They have strong colors and beautiful lines, inspired by the Dunhuang murals. We also went to Xi’an, were we saw all kinds of ancient objects, as well as to Lanzhou, which is also in the west on the way to Dunhuang, famous for ceramics and for large rock sculptures. I feel that ancient Chinese art is very spiritual—much more so than western art, it seems to me. This moved and inspired me. We also climbed Huashan, the huge mountain very famous for its narrow and dangerous path. I climbed the mountain and felt a real sense of achievement. Just a few of us climbed it.

PG: What did you and your fellow students discuss outside class?

GZ: Mostly we discussed why we did not have freedom to create art works. We talked about Picasso and Dali’s work and their life stories—so fascinating. Sometimes we talked about some of our teachers’ life stories. Who did what, and whose paintings were more interesting. I remember the first time we saw Charlie Chaplin’s movies; we couldn’t stop talking about them. I was really very focused on study during my time at college. I think most of the students were very thirsty for education. During the Cultural Revolution no one went to college, and I really wanted to make the most of my time there. There were only thirteen or fourteen students in the Chinese Painting Department at the time. More than 10,000 people applied for the fourteen slots, so the competition to get in was intense. Once in, there was lots of pressure to excel. Then, when we started to get the opportunity to express ourselves, I did my best to excel. My efforts were rewarded when I was asked to remain in the Academy’s Chinese painting department as an instructor, the first woman to be so honored since the Cultural Revolution.