十年来,中国新建了五千余座博物馆,兴起了博物馆的浪潮,其中既有针对考古、自然史的博物馆,也有针对当代艺术的美术馆。有人会说,这些建筑只是金玉其外,败絮其中,展览问题重重,对于历史的叙述带有过分强烈的意识形态色彩,此外,用于展览策划的资金不足,往往得不到公众的关注,等等。另一方面,对于城市规划和形象推广而言,博物馆具有品牌效应,是“建筑中的路易威登”。但从建筑方面而言,其中也不乏独具匠心者。Clare Jacobson在其著作《中国新博物馆》(New Museums in China)中回顾了新千年以来在中国出现的各类新建博物馆,如其所言:“建筑已经远远超越了策展研究与艺术收藏”。至少,在充裕的资金、频繁的土地购置,以及对于建筑保有浓厚兴趣的条件下,中国成了全球建筑师的大舞台。

Clare供职于普林斯顿建筑出版社长达21年,现任编辑部主任。目前她是《建筑实录》(Architectural Record)特约编辑和撰稿人。

就中美两国的博物馆和城市规划等问题,本人对Clare进行了采访。她将博物馆比喻成“建筑中的路易威登”,让中国的城市趋之若鹜,试图重新创造出“毕尔巴鄂效应”。1997年,弗兰克·盖里(Frank Gehry)设计的古根海姆博物馆让这座城市焕然一新。Clare说,纽约的大都会美术馆在开始艺术收藏之前就建造了第一座建筑。她认为,对于博物馆而言,建筑应首当其冲,然后才能谈展览项目、策划和收藏。她说,中国充满了异想天开的建筑,有各种各样的写字楼大厦,但它不仅是一座座钢筋混凝土结构,而是独特的建筑。这些建筑也许会成为博物馆,或者成为文化氛围的基础。

她谈到,一座城市的复兴并非纸上谈兵。旅游业无疑是城市的重要经济来源,也是能够迅速带来利润的产业。每座城市都希望吸引更多游客,其中,博物馆就扮演了重要角色。她说:“西方博物馆发展的历史告诉我们,博物馆浪潮即将来临,因为人们会对博物馆当前的情况进行反思,也更希望看到更好的博物馆出现……欧洲曾经也挖苦那些博物馆没有内容,但放大来看,一座建筑又能怎样?对于中国的大趋势而言,博物馆无足轻重。”

以下是英文原文采访:

Daniel Szehin Ho: How did the book get started? What caused you to write this book?

Clare Jacobson: First off, I have always been fascinated with museums, having grown up in Philadelphia. Since then, I’ve been one of those museum tourists —not only to see the collections, but also the buildings. In Shanghai, I saw a museum being built near my house; then I found out about all the other museums—I knew there was something to it.

DH: You had been working with the Princeton Architectural Press, hadn’t you?

CJ: I was the editorial director and had worked with them for 21 years; I joined straight after getting my architectural degree. I did little writing then; it wasn’t until I moved to China that I begin writing. This, frankly, was due to my contacts in the States. I write primarily for Architectural Record, where I’m a contributing editor.

DH: So is there a particular “architectural book” genre which New Museums in China belongs to?

CJ: Well, it’s an architectural survey—a fairly standard way to look at architecture. You look at, say, hotels in Thailand, or gallery spaces—a building type.

DH: And in terms of area?

CJ: No, not so much in terms of a particular area—I had trouble getting this picked up. People asked, “Why not new museums in Asia?” But the museum boom is happening here by necessity—state funding, private funding, developers. It’s happening here.

A lot of these books more typically survey something like new museums throughout the world. “New Architecture in China” is very specific.

DH: On the other hand, since there are so many new museums, your book is pretty small, no?

CJ: We know there is a phenomenon—an important phenomenon. One that might be at its end.

DH: Why is that?

CJ: It remains to be seen. For instance, the NAMOC museum (architectural design contest) winner, Jean Nouvel, took a long time to be announced. There is some speculation that in fact, the new anti-corruption austerity measures might be affecting not just “extravagant spending,” but museum spending as well.

DH: I was quite surprised that the NAMOC architect would be French. In a lot of countries, such a site is fraught with symbolism…

CJ: I can’t think of the Smithsonian being designed by anyone other than an American. With private museums, it’s different.

DH: You mention how museums have become “the Louis Vuitton bags of architecture. Every city in China wants one now.” There are many attempts to reproduce the “Bilbao effect”—the rejuvenation of a city through museum building, following Frank Gehry’s successful 1997 Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. To be snarky, it all seems a bit fake and hollow.

CJ: Okay, sometimes it is fake. That said, the Metropolitan Museum in New York actually acquired its first building before its first piece of art. Building is going to come first. Architecture has just advanced well beyond curatorial studies and art collections. The buildings come first, and me being a wonderfully optimistic person—after that comes programming, curation and collections.

I also recognize that some of them won’t. There’s a lot of speculative building in this country—office towers and so on—the difference here is that you get a great piece of architecture, instead of a concrete tower. I hope they turn into viable museums, or at least provide the infrastructure for cultural venues.

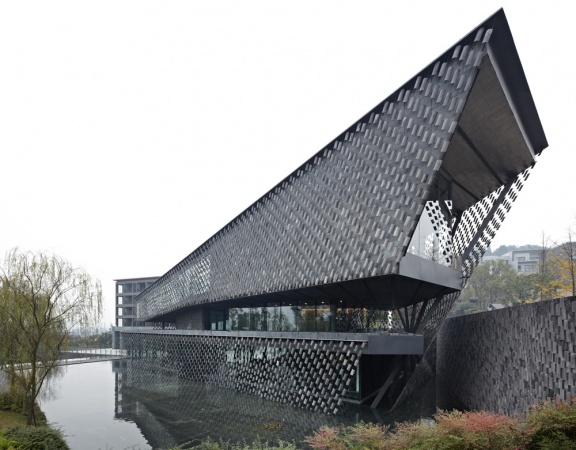

Xinjin Zhi Museum, Xinjin, Kengo Kuma and Associates. CREDIT: Daici Ano

新津志博物馆,成都新津, 隈研吾建筑都市设计事务所,图片提供:Daici Ano

DH: Sometimes people in the arts have high expectations. In some ways, having that architectural statement is itself important.

CJ: Yes. Urban development depends on well-established icons. The model of “town hall, church and square” won’t work for China. Maybe it will be more like the expo—performance center, art museum, two exhibitions…and a mall, and maybe a museum.

DH: Aren’t malls more of a center than museums?

CJ: Definitely, they accept more people and attract more interest. Maybe we’re not just about culture.

Look, at least these museums break up the monotony of urban planning in China—other than stand-alone buildings amid the endless stream of residential skyscrapers and commercial towers.

DH: So isn’t this all a bit fake?

CJ: The rejuvenation of a city is not a fake thing; it’s a reality. How much influence did Gehry have in Bilbao? Maybe it was already coming back. There is no doubt that tourism is a huge part of a city’s economy—it’s the quickest part of the economy. Every town makes efforts to bring visitors in. Museums are a key component.

DH: Iconic architecture is also a tool of national branding.

CJ: In new towns throughout Asia, there’s this master plan with an iconic building—some sort of a tower. Museums are somewhat different—especially because they’re on ground level. New York has its skyline, but the Guggenheim is on ground level. There’s a different kind of icon and architectural experience.

DH: I noticed some museums mentioned in your book aren’t going to happen in the end.

CJ: The book took one full year to publish, so I had to rely on the information available at the time. I don’t claim to understand the intricacy of building developments—they are huge, with plans which may be presented to investors detailing certain images of the development; then there’s the waiting for the other parts of the plan to come to fruition. It has to do with some power politics.

DH: The influence of Chinese museums is really low, in the end.

CJ: When you look at the history of museums in the West, in the US, it just takes time. It will happen. Because there are enough people critical of the current state of museums, there are enough people interested in making it better.

China Wood Sculpture Museum, Harbin, MAD Architects. CREDIT: Xia Zhi

中国木雕博物馆,哈尔滨,MAD建筑事务所,图片提供:Xia Zhi

DH: Actually, I wonder how museums die in the US?

CJ: A lot of small house museums and historical museums are dying a sad death. As for big museums—well, instead of dying, they change funding programs. You know, like Bank of America at the Met. It’s not how they die, but how they stay alive.

Of course, there are changes in building types: armories which are now performance centers, or a bank hall in Brooklyn used as flea market. There’s all this repurposing of churches, for instance, as restaurants, bars, performance spaces…

DH: Or even turned into lofts…

CJ: They are retained because they are on a specific spot with architectural value. People think they are worth keeping.

DH: What about in China?

CJ: I think the buildings with greater significance will be kept.

DH: In China, there are so many museum/cultural/design clusters. Is this common in the States?

CJ: First off, there aren’t a lot of new towns in the West. But historically, say in Philadelphia, there is an axis of a big avenue downtown, positioned in a prime location, with museums around it. New York has Central Park with the Met alongside it. And New Museums in the Bowery—now everybody goes.

There was a museum building boom in the US at the end of the 19th Century. Then, it was much as it is now (in China). Those museums were positioned there and then for effect—Philadelphia, Chicago, New York. Museums now don’t have that scale, since they can fit themselves into the urban fabric. I’m sure Europe was remarking that there was nothing inside the museums, either.

In China, there’s a new specific type of museum, with exhibitions and other events, where you have a floor of art and a floor of shopping mall. In some ways, K11 has more programming than any museum in China. Who says the Western model is the only model?

At a certain time and age, even in the West, single buildings had more import. Now, the current generation [in the West] are much more interested in the urban fabric. At the same time, when I walk through some parts of Shanghai, where it’s ugly and monotonous, I’m generally happy to see a building that’s “beautiful” (I suppose “beauty” is another word the younger generation doesn’t use). Out of all these buildings, significant buildings by significant architects are an important thing.

DH: Ha! The younger generations are all vegetarian hippies into Jane Jacobs and the “urban fabric”…

CJ: It’s a phase; they’ll get over that. They are more realistic and less optimistic than I am—and that’s fine. In the grand scheme of things, what does a single building matter? Museums aren’t so important, for the overarching trends of China.

Sifang Art Museum, Nanjing, Steven Holl Architects. CREDIT: Shu He

四方当代美术馆,南京,美国斯蒂文•霍尔建筑设计事务所,图片提供:Shu He