Most visitors to “Great Performances” were likely struck by the extraordinary range of works the exhibition presented, but what they actually made of those works, or of the exhibition as a whole, depended upon their knowledge of performance art in China (or in general). It also mattered how much each visitor cared about the matching of artworks to an exhibition title or theme. For me, “Great Performances” prompted reflection upon the role of a commercial gallery in promoting art of a radical nature—which habitually and electively sits outside mainstream practice—but left the question hanging.

First, though, the “extraordinary range of works.” Given the siting of this exhibition in a leading commercial gallery, it was not wrong to expect the works on display would be by artists of some significance. Pace, after all, is a “taste-maker” for collectors, which naturally makes its tastes of particular importance to the artists the gallery shows or doesn’t show, as the case may be. But the act of affirming individual artworks through exhibiting them is not equal to the validation of an artform, and one as difficult as performance. Perhaps for this reason, the term performance invoked here was somewhat misleading. For one thing, there were no live bodies present in the space: all that was awkward and potentially disturbing was contained in the safe borders of a photograph, or within the confines of a projection or video. To recreate performance works in venues or at times to which they are unrelated is a sticky issue. But unpicking the history—context and meaning—of performance works ought to have been part of an exhibition with a title like “Great Performances,” and which described its objective as interpreting “the occurrence, development and status quo of Chinese contemporary art (mid-1990s to now)” (1). Clearly such an objective necessarily requires more circumstantial material than a commercial gallery finds it appropriate to provide. But perhaps that’s open to debate.

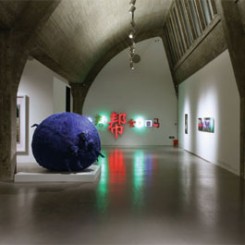

On the plus side, a good number of the works included in “Great Performances” represent the finer points of the individual artists’ career: Wu Xiaojun’s brilliant string of luminescence “Gift” from 2006 verged on the sublime. As a gesture, it is simplicity itself: a series of neon tubes that appear to have been gently hand-crafted and painstakingly strung together to achieve a faltering upward trajectory that is both haunting and determined, vulnerable as well as otherworldly. “Gift” was previously shown in 798 in an exhibition titled “Enemy at the Gates” organised by 798’s renegade-founder, Huang Rui, in 2006. However, that previous presentation failed to display it to such effect as in “Great Performances”: here, it felt positively exalted, its inexorable air of fragility a prescient reminder of the zeitgeist of this present age.