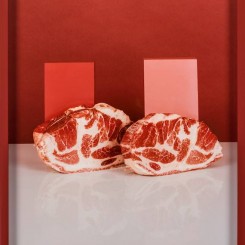

The game of guessing where the image was taken, so familiar from Bresson and Riboud, does not work here. See, for instance, the flat plasticity of “Boston Shoulder Roast” (2012), a small-scale framed picture showing two pieces of thick steak standing on their edges. The marbling of ivory-white fat and cherry-colored flesh is placed in an antagonistic relation with the straight lines of two pieces of paper, in vermilion and pink respectively, placed in front of a crimson background. Echoing a familiar commercial visual topography, the image somehow resembles the Panzani advertisement Roland Barthes commented on in 1964. His analysis of the Italian food commercial juxtaposes semiotic structure with the composition of image and text in the advertisement; despite the resemblance between the two images, however, the linguistic or symbolic messages conveyed in the advertisement are absent in Lassry’s meat photo. What is left in its place is a void constructed by the image, which “straightaway provides a series of discontinuous signs” in the words of Roland Barthes. The sum total of directional semiotic operations in the visual narratives of advertisements marks a contrast to the assemblage of objects in the discontinuity encaged in the totality of the image, even if they share similarities in structure. Through this discontinuity, Lassry’s photo parades an artistic allure, defined by Graham Harman as an “intermittent experience in which the intimate bond between a thing’s unity and its plurality of notes somehow partially disintegrates,” pushing a sensual object to a certain distance no matter how close the audience gets to the artwork.

Always a talking point around Lassry’s practice, the trademark colored frame acts as a transgression across the photographic boundaries that demarcate and contain the totality of the image, thus making the image so. “The image is always sacred,” says Jean-Luc Nancy. Here, the sacred is opposed to the “religious,” as the latter implies a bond and the former “signifies the separate.” Photography is seen as a moment in which reality cuts off from itself, forming a distinct capacity that is withdrawn from the “world of availability,” in Nancy’s words, while at the same time setting up a passage that never passes. This is the framing that makes photography.

Another concept of enframing, Martin Heidegger’s “gestell,” is a “mode of revealing that holds sway over the essence of modern technology but which is itself nothing technological” (Martin Heidegger, “The Question Concerning Technology”), is explained by Harman as reducing the “the world to a stockpile of presence-at-hand.” Nancy and Heidegger both discuss the enframing of the reality and image. The visual structure of photography builds a gap of asymmetrical parallax along with the conceptual enframing of the perception on the medium, allowing one perspective to elude the other. Lassry’s “Untitled (SP Yellow Cabinet)” (2012) deepens this discourse of enframing: in a line of five canary-yellow cabinets, two are equipped with frame-like doors set with tempered glass, while the rest are enclosed with solid doors. The yellow doors enframe the physical space of reality as constituted by our sensual interpretations and experiences, sharing the same space with the audience and warning us about the gestell in our reality by juxtaposing the presence of enframed voids within a single art object.

Painted frames implement the transgression of the photographic images across the distance from the order of touch —away from us. They are windows to the viewer, merged with the theatricality constituted by the image-objects and the floating negative space around them. They erase the divisions between the perceptual architecture of space as we understand it in everyday life and linear perspective as artistic form anchored at the vanishing point or points. This is another erasure enacted by Lassry’s frame: it intrudes into the physical space of the audience as part of the image (and the image portion of an object) instead of acting as a classical neutral interface that does not belong to either side. “Untitled (Wall, Hong Kong)” (2012) works as an example of this mechanism: it includes a freestanding wall built in front of a gallery wall, smaller in size and with six date-red ceramic objects in the shape of the lowercase lambda sitting on top of it. The gallery wall behind is hung with black and white photographs also numbering six. Putting aside the possible interpretations of Greek origins, what is at stake here is the fluidity of perspectives generated by the installation. Regarded from different angles, the photographic installation produces diverse spatial relations between the objects and images according to the changing position of the viewer in the gallery space. Conflicts between the fixed, single linear perspective of the images as determined by the photographer and the fickle spatial perception of enframing as initiated by bodily movement of the viewers stage a vortex in which the subject is not defined by an external gaze from a distance but rather objects of linear perspective where anchoring to a fixed center is impossible. The omnipotence of photographic vision is dissolved by the ontological frame and material existence of photography per se — a paradoxical or even oxymoronic gesture of precisely the sort that should appear in art.