Ground Control to Major Zhang

And if these subjects can seem too sickly sweet — sometimes they clearly are (e.g. “Night” (2007), a nostalgic view of a couple under a Chinese parasol watching something, possibly at an outdoor cinema) — then we must ask to what purpose, because it is not possible to just sit forever in mindless reverie with epic tableaux of ash — even “Night” — that recall some of the harshest periods in China’s long history. And this is the point. Zhang Huan is not interested in telling us about what he may or may not recall, but what we do, that is, his fellow Chinese. The series of “Memory Doors” are just another way of presenting this conundrum (also the contrast, such as the numerous intricately carved scenes on old doors proudly presenting technical wonders, like a line of radio telescopes, “Memory Door Series (Afar),” 2009). These works also speak to Buddhist mysticism and socio-cultural pride, albeit with the deliberately awkward anachronism of employing wood and silk-screen to do so).

China has developed massively in the intervening two decades (beyond the Id-jungle of the blogosphere), but as people become more critical, public critique remains barely tolerated. The authorities have become more sensitive to (their) image management, and even the notion of criticism, perniciously tied to the shameful history of the Cultural Revolution, is feared. And as we have seen with Ai Weiwei, the more prominent the public figure, there is a greater expectation of compliance, with the Party, with assumed proprieties. How then to utter the unspeakable? Zhang Huan’s art is full of quiet outrage, the anger of being coopted by history — survivor’s guilt and generational compromise. It is unwavering, even if the artist himself must dance to mark his space, albeit with a certain protection afforded by his fame, for what that is worth. It is also an act of memory. One of the most fundamental acts of individual freedom is not to forget, and one of the most fundamental individual responsibilities is not to allow others to.

Sichuan Earthquake

When “Grand Canal” was first shown at the Shanghai Art Museum as part of Zhang’s “Dawn of Time” exhibition, it seemed an odd inclusion in an otherwise installation-heavy display. In retrospect this giant gash of a painting, surely refers to the 2008 Sichuan earthquake — which killed over 60,000 people — as much as the folly of these vast projects of the Great Leap Forward (1958-59). (5) The earthquake caused a social rupture in China as much as a geological one. The Internet, mobile telephony, and a bigger, even freer, press meant images of the devastation were quickly broadcast around the country and independent volunteer networks were established.

Zhang responded to the loss of life in numerous works, in one case problematically. He travelled to the earthquake zone and assisted victims of the carnage. And he also adopted a famous pig that had survived the destruction, trapped for 49 days without food, Zhu Gangqiang, the “Cast-Iron Pig.” These 49 days — mirroring Zhang’s own feats of endurance — correspond to the period according to Buddhism that the ordinary soul (neither pure nor wicked) spends between death and transmigration, and during which it searches for the conditions of its rebirth. Accordingly Zhu Gangqiang subsequently became a leitmotif in various works, peering out of “Pagoda” (2009), a smoking bell-shaped temple constructed of reclaimed bricks (disturbingly reminiscent of an oven), and also the basis of Zhang’s first exhibition at White Cube in late 2009, which included a live-feed video of the pig at Zhang’s studio while two real pigs became pungent residents in the gallery itself. (6)

The same year came “Hope Tunnel” at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art. At once numbing and operatic, the installation of a train mangled by the earthquake forced visitors to walk through and over the wreckage, as if over an old battlefield. And it remained breathtaking right up until the moment one read the accompanying publicity, which involved emoticon descriptions that accorded with the government narrative of sympathy without analysis, that is, reducing the rage and shock of the installation to mere sympathy. For example:

…Every so often there comes an event that rattles our faith, shatters what we have built and shakes us to our very foundations. The 2008 Sichuan earthquake was one such tragedy. No one who witnessed the terrible destruction and loss of life will ever forget it. Yet in the aftermath of tragedy there is hope, a reminder of what people working together can achieve… (7)

Why problematic? Because the debate as to why so many buildings collapsed, particularly school buildings, killing so many, was silenced. Who was responsible for this curatorial gloss, this crude appropriation of empathy? Was it censorship, or self-censorship? Uncritical complicity was unnecessary, — is that a fair comment? Like many Chinese artists, unrealistic (Western) expectations are sometimes projected onto Zhang. After all, an autocracy is really post-modern: eventually everyone gets appropriated. Other artists though took a different path….

__________________________

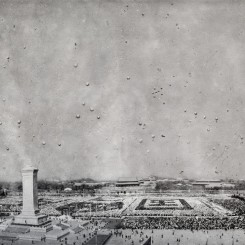

5. The image derives from the 1972 issue of China Pictorial, a magazine from the Cultural Revolution period (1966-76).

6. “Zhu Gangqiang,” White Cube, September 3 – October 2, 25-26 Mason’s Yard, London. “Pagoda” also references Zhang’s early performance piece “Peace,” (2001) in which a gilded life-size statue of Zhang is the hammer for a Buddhist temple bell inscribed with the names of people he knew from his village. Another of Zhang’s familiars is a priapic donkey who fucks skyscrapers – Shanghai’s Jin Mao tower (“Donkey,” 2005) – and leaps out of piles of bricks reclaimed from demolished old houses (“Dawn of Time,” 2010).

7. Here from the e-flux announcement:

Every so often there comes an event that rattles our faith, shatters what we have built and shakes us to our very foundations. The 2008 Sichuan earthquake was one such tragedy. No one who witnessed the terrible destruction and loss of life will ever forget it. Yet in the aftermath of tragedy there is hope, a reminder of what people working together can achieve. Zhang Huan’s Hope Tunnel, a curated social project at UCCA, was conceived and designed by an artist who believes that art has the power not just to move us emotionally, but to galvanize us into positive action. When we behold the train that Zhang Huan purchased, refurbished and installed here, we may find ourselves dwarfed by the scale of the wreckage, dismayed by the destructive force of nature and daunted by the challenges that lie ahead. Perhaps we should feel humbled by the shadow of that awesome bulk, but as the title reminds us, while we may be small, we are not powerless. Through remembrance, reflection and concerted action, each one of us has the power to help—and to hope. [e-flux announcement for Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, July 9, 2010.]