@What — New Contemporary Art from China (May 30th to August 11th, 2013) was held at the ArtMIA Caochangdi Space, Beijing, and was created to mark the twentieth anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of Korea. This exhibition was co-organized by the National Art Museum of China and the Korean Art and Culture Committee, among other official organizations from both countries, and was previously shown as a traveling exhibition around Korea. Randian interviewed the curator of the exhibition, Ms Liu Chunfeng, who also works for the National Art Museum of China. This interview offered an occasion to gain a better understanding of the Sino-Korean dialogue in the field of contemporary art, and of the appreciation and understanding of Chinese contemporary art on behalf of the Korean public, which is very similar to the Chinese public from a geopolitical and cultural point of view.

Randian: Although the title of this exhibition is “@What — New Contemporary Art from China,” it does not only present works of emerging artists, but also some by established figures in the world of contemporary art, such as Xu Bing. So how do you define “new” contemporary art?

Liu Chunfeng: By using the word “@what” in the title of this exhibition, our intention was to convey a message regarding the linguistic categories of contemporary art. The “@” and the “what” in this title refer to the verbalzsation of artistic concepts. Therefore, when selecting the artists, I took note of whether they used new artistic material and concepts within their works, and whether this new material and information stimulated their creativity enough to make their artistic concepts and ways of thinking undergo some kind of radical change. Thus the word “new” here does not refer to the age of the artists, but only to characteristics of their artistic language and concepts, and all eight artists are quite remarkable in this regard.

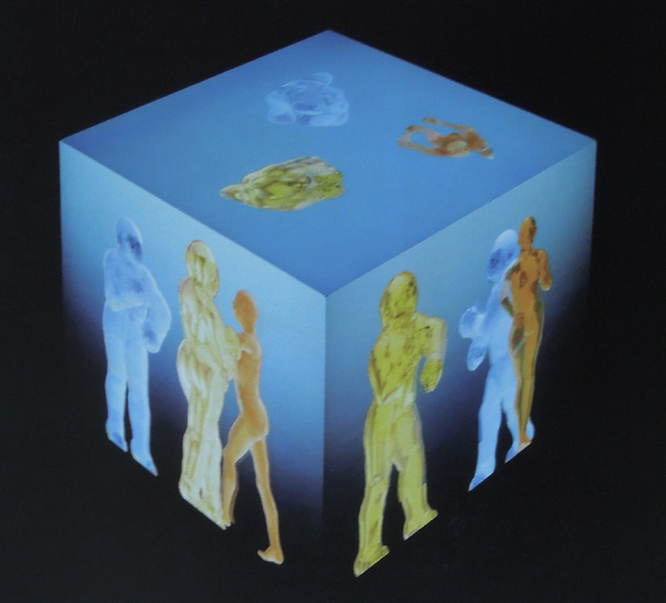

Miao Xiaochun, “The Neo-Cubism-Out of Nothing,” 14’00’, 3D animation installation, 2011-2012

缪晓春,《新立方主义-无中生有》,14’00’,三维影像装置,2011-2012

Randian: This exhibition was created to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Korea, and has been shown in both countries. So what image of Chinese contemporary art are you trying to convey through it?

LCF: The friendship between China and Korea runs very deep. In 2007, for the fifteenth anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations, the National Art Museum of China (NAMOC) also participated in an event under a similar cultural framework. That year, we collaborated with the Korean National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art on a project called “Floating”; I was lucky to be chosen as one of the curators, which led me to work with Mr. Fan Di’an, the director of NAMOC. But of course, trying to provide a complete overview of Chinese contemporary art through a single exhibition is not very realistic.

Randian: So what do you think are the main aspects through which these transformations can be observed? Or are there any trends to speak of?

Liu Chunfeng:As a matter of fact, through this exhibition we want to raise an academic question, or perhaps an attitude. It goes without saying that everyone, be it art scholars or the public, can take part in discussing the questions about the current state of contemporary art. As we all know, Chinese contemporary art has undergone many changes, for instance when it became accepted by the West in the 1980s, and received no small measure of recognition from both the academic field and the art market — which was linked to the creation, by contemporary Chinese artists, of an avant-garde discourse. At that time, the most fashionable styles were very symbolic and political, like Pop Art for instance. Formally speaking, symbolism and minimalism were easily accepted by the Western public, and easy to deal with for the market. But for the last 20 years, contemporary Chinese art has slowly moved from the outside in, and as for the artists, they have abandoned simple conceptual artistic creation and come back to their roots.

Xu Bing, “Spring, River, and Flowers on a Moonlit Night,” painting size: 187 x 98 cm; total vertical size: 277 x 98 cm, ink on paper, 2012

徐冰,新英文书法-《春江花月夜》,画心尺寸:187 x 98cm,立轴尺寸:277 x 98cm,水墨纸本,2012

Randian: The “@” can actually be considered as an archetypal logo of the information age. But it seems to me that concepts such as those of information age, informatization, or globalisation, have become universal values in reality. How can such universality stand for the unique cultural and geopolitical features of Sino-Korean relations?

LCF:Because this exhibition was primarily established within the framework of the twentieth anniversary of the establishment of Sino-Korean diplomatic relations, it was necessary to find a theme that would speak to both countries. As you said, the “@” is a universal value which transcends local Asian values, and has become a symbol of globalisation. Besides, for the Korean, the “@” logo is not as new and exciting as it is for the Chinese, because the latter have entered the “age of twitter” or “age of weibo” for no more than two or three years. For the general public, this is something fresh, and the process of obtaining a symbol from the refinement of a universal object or value can also reflect the transformations that occurred in the field of arts and artistic creation.

Randian: Apart from providing the event venue, how was the ArtMIA Foundation involved in this project?

LCF: In 2007, the ArtMIA manager Ms. Chen Xuanmei participated personally in the sponsoring of the cultural activities organized for the fifteenth anniversary of the establishment of Sino-Korean diplomatic relations, and simultaneously sought some Korean support. In 2009 she established the ArtMIA Foundation, in order to stimulate exchanges and projects in the field of contemporary art in Asia and especially between China and Korea. She also enthusiastically participated in this project, which thanks to her efforts was granted financial support from the Korean SK Group. Moreover, before this exhibition was set up at the ArtMIA Space, it was also shown at the museum of the Korean Arts and Culture Committee (ARKO), so we can say the exhibition has now travelled to China. Of course, this required us to adapt a few of the exhibited works to this different exhibition space. For instance, while we showed the works of Wang Wei in Korea, due to a variety of factors — technical and space-related — we replaced him for the Chinese exhibition by Guo Lijun, whose photography work was carried out in the area around Caochangdi, as luck would have it. After the exhibition in Korea, the ArtMIA Foundation showed great dedication in presenting it once more, this time to the Chinese public.