“Each of these interventions has a place in history, and many fed off each other as well as the circumstances of the society and the art scene they were intended to defy or, arguably, to defile.”

“The mediation of random text—quotations from the artists out of context, or from philosophers / theorists whose connection to the artists is unclear—for me, at least, intruded upon viewing and interpreting the works. Some kind of historical timeline or overview would have helped set the scene for those more dramatic videos of actual performances.”

“This type of work cannot be separated from the context either in which it was conceived, actuated, or, latterly, in which it is presented. It is an extreme act, with little in the way of redeeming features, laced with anger, violence and isolated solitude, hopeless helplessness.”

It doesn’t matter that, in addressing an art form that does not have a high profile in the art world, “Great Performances” would include artists as yet unfamiliar to viewers. What does matter is that there was no real attempt to address the unfamiliar, either the complexities that underscore performance art, or the forms it has adopted and embraced. The mediation of random text—quotations from the artists out of context, or from philosophers / theorists whose connection to the artists is unclear—for me, at least, intruded upon viewing and interpreting the works. Some kind of historical timeline or overview would have helped set the scene for those more dramatic videos of actual performances—Yang Zhichao being one, Wang Qingsong another, and Ma Qiusha. All could be seen as shocking but, equally, each illustrates the extremes to which such artists were willing to go to make themselves seen and to be taken seriously; ergo, the most extreme of works from Zhu Yu, like “Skin Graft” and “Eating People” (both 2000). In “123,456 Chops,” Wang Qingsong performs a death by a thousand cuts on the corpse of a dead goat. We are not privy to the manner in which the goat met its death, and are instead forced to wonder and to imagine why the artist chose this mode of expression. This type of work cannot be separated from the context either in which it was conceived, actuated, or, latterly, in which it is presented. It is an extreme act, with little in the way of redeeming features, laced with anger, violence and isolated solitude, hopeless helplessness. In the artist’s words, it is specifically “imbued with the general attitude, personality and character we are taught is the ideal male in Chinese society,” which is perhaps hard to reconcile with the newly minted image of the “metrosexual male” in Western society. Its placing in this “blue-chip” gallery was awkward and made a theatrical, callous gesture of what was a consciously constructed act.

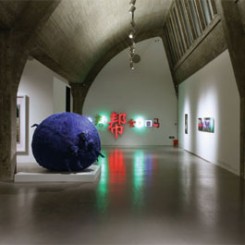

The main reason that “Great Performances” feels like an opportunity missed is that it is arguably the first exhibition of its kind to take place in Beijing and could have marked a milestone in its art history. It says much about the perception of galleries, about success, and about achievement in in the Chinese art world that artists who have successfully navigated the complexities of live performance within the constraints of the highly controlled or watched public arena find it now natural to present their demonstrative stands against social convention, mores, and controls in mainstream, albeit elitist, galleries. In terms of art, Beijing Commune would have been so much better suited to the task, but to return to the analogy of punk, this type of exhibition makes the unknown / abnormal safe.