David Zwirner: Maybe we should start at the beginning and talk about how we met, how we got to know each other. It is exactly 20 years ago, 1992, that I saw your work for the first time in Jan Hoet’s documenta.1 I didn’t know your work and I remember going into the container, into the additional buildings that Jan put in the park, and being immediately intrigued, but mostly puzzled. I remember trying to make sense of what I was seeing. That body of work was from the 1980s through 1992, right?

Luc Tuymans: Yes, there was a definite choice not to show any new work at documenta. I had a show coming up with Ulrich Loock 2 and I was afraid that the whole situation would speed up so much that it would have an effect on the integrity of the work.

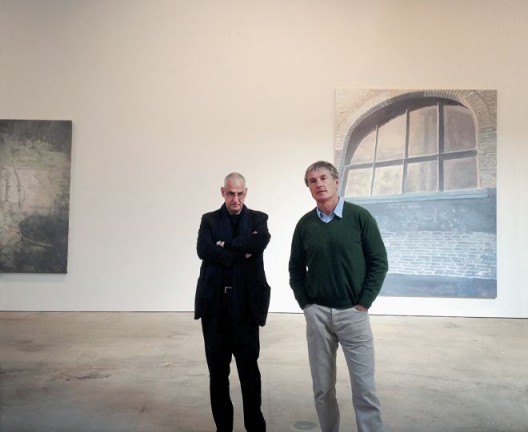

Luc Tuymans and David Zwirner at the 2013 opening of “The Summer Is Over” at David Zwirner, New York

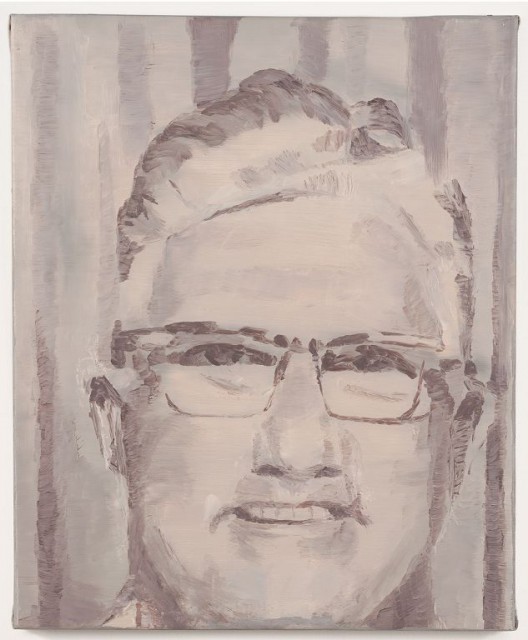

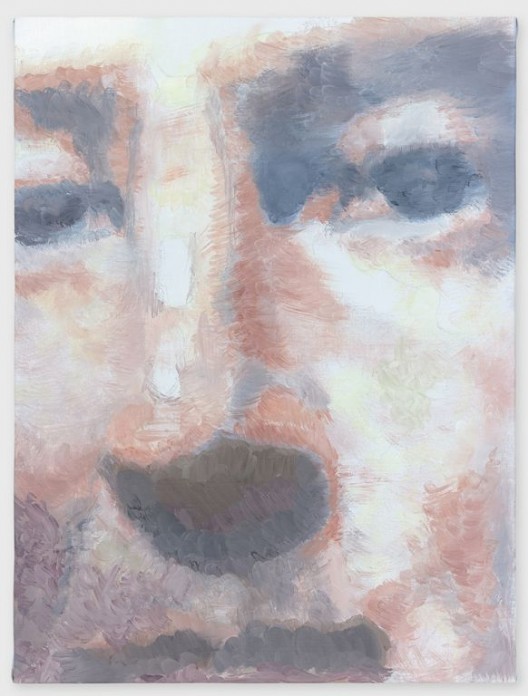

Zwirner: I remember being confused because the work was hovering between figuration and abstraction. I was confused that the scale was so modest and the work so powerful. But most confusing for me was the issue of dating. The work had a patina and these early paintings were often layered. You would create multiple layers, the canvas was distressed and there was a poverty in the presentation of these very simple small canvases that made me think: when were these paintings made? I asked Kasper Koenig to put me in touch with you. He was the one guy I knew, at that time, who had clout. Of course I didn’t have a gallery yet, I only had the plan to open a gallery. Kasper gave me your phone number and then we met in Antwerp. Before you finally agreed to do a show, I remember that I had to come to Antwerp three times and make my case.

Tuymans: Yes, and the third time I asked you what you thought was interesting at documenta besides my work, and you said you liked Stan Douglas’s work.

Zwirner: Yes, Hors-champs (1992) and Monodramas (1991).

Tuymans: Major work in that documenta. You said that you liked them and that’s in part why I agreed to join your gallery.

Zwirner: And then, of course, I began to show Stan as well. So maybe you reinforced my views. It’s interesting: this being a documenta year, I feel we have to give Jan credit. He got a lot of criticism at the time, but in hindsight, it was an important show. There were a lot of very important artists.

***

Zwirner: That is a nice gateway to your work because you came to prominence at a time when people assumed painting was finished. Painting was marginalized and it was no longer considered a relevant medium. The media that became prominent were large installations and film and video. Yet, somehow your work made it into the important exhibitions of that period. I think it was admitted because it looked as if it had come to terms with the fact that painting was finished. Due to its small scale and seemingly modest approach, it almost looked like “Oh, here’s a painter who understands where painting’s place is.” But, of course, that was a Trojan horse because you ended up bringing painting back.

Tuymans: Yes, the first time I met John Baldessari, he congratulated me for what I was doing for painting. It was strange because in a sense what I do is quite traditional. I think that’s exactly the point about painting: its essence is to be central and traditional. So eventually, after being pushed to the periphery by the dominant discourse, the fact of its absence became incredibly important. But that was to be predicted. Paintings were the first images to be conceptual and therefore artistic. In a sense, denying painting is denying the visual itself, especially when we talk about Western culture. That’s what makes the continuation important.

Zwirner: Your contribution is particularly important because although you’re often considered a postmodern painter, in the true modernist fashion, you created your own vernacular: a new vocabulary. A Tuymans painting is a type of aesthetic. And I know you didn’t want to create an aesthetic, but you did and it exists now. So you created something new. And that gets harder and harder to do in painting, which is why the curators in today’s world are looking to other media where there’s a little more room to maneuver.

***

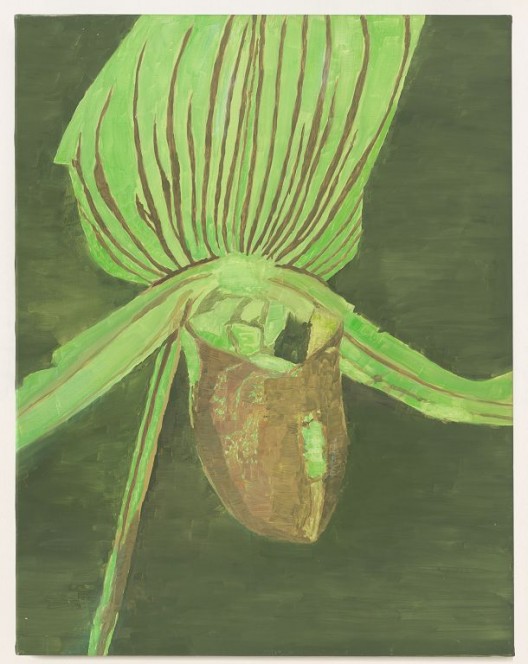

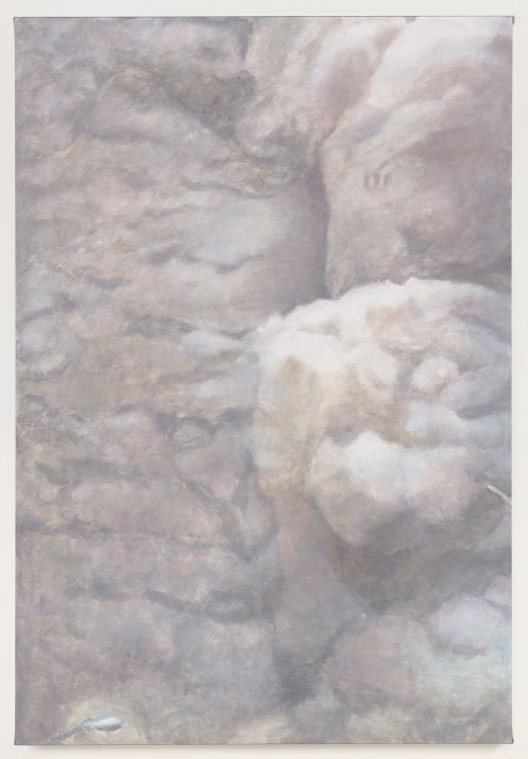

Zwirner: Let’s talk a little bit more about the change in painting. You were talking about the fracturing of the images. I saw the change of the brushstroke the first time in Demolition, where you can see each stroke as you walk closer, and I remember seeing the same thing in Magic: you look at an automaton, a machine, and as you walk up close, all you see are brushstrokes. The painting style had evolved.

Tuymans: It was due to the use of this one color, and the fact that slowly but surely a new idea of contrast was developing. It also had to do with the idea of projected imagery. It is important that there was a very filmic element or cinematoscopic idea in many of those paintings. It had to do with the digitalization of the imagery because most of the source images came from websites.

Zwirner: Talk about that for a second. There is a trajectory in the source material. When I met you, you were working from found images.

Tuymans: Or drawings, or watercolors.

Zwirner: Then the Polaroid became more and more important.

Tuymans: In 1995, yes.

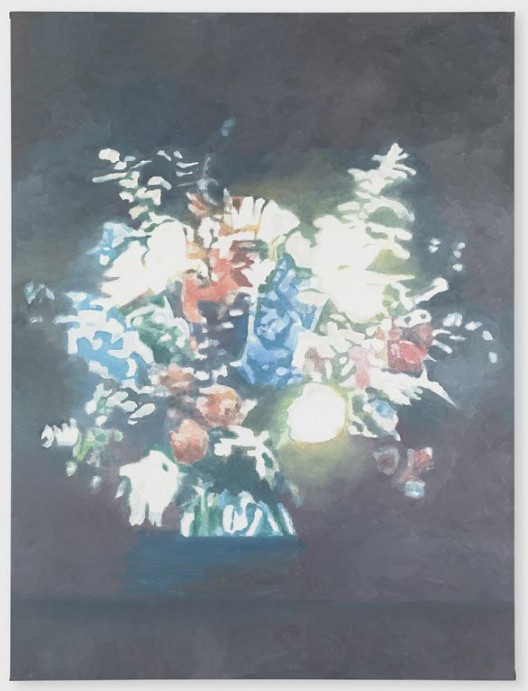

Zwirner: Exactly. There was this light from within the paintings. Because the Polaroids used flash, you had a sort of overexposure that entered the work. There are many great examples —Drum Set (1998) comes to mind first and foremost—of this luminescence in the painting. Then in a pretty radical change, the Internet became central, as did the screen. There were works based on photographs of TV screens before, but with the Internet, the imagery came straight from the screen. The photos you take with your iPhone are great examples.

Tuymans: I think this is one more interesting and exciting point. Instead of fighting the new media, which is ludicrous to begin with, the screen is something that is taken in. It is incorporated in the decisions about of what to paint. Forever: The Management of Magic is very important in that sense because I chose what had already been depicted. It was both known and unknown.In the upcoming London show, you will see more of that because parts of my silhouette are mirrored in the painted screen of the computer from which these images were taken. The layers become more and more complex. And therefore the painting style has a different urgency to it.

Zwirner: That’s one of the things that strikes me about your recent work. You really create the contemporary image. I think that is actually quite hard for people to navigate. They see an image that has been mediatized to the nth degree, but it is painted in a very traditional medium. There’s a real disruption between these two things. It should be a digital image but it is the most analog image of all. I feel that’s something that isn’t spoken about enough: the issue of creating the most contemporary images based on the prevalent technology without being gimmicky in the process. There is a certain kind of light that comes out of a screen and you can find that light in your paintings. It’s almost scary when it comes back at you from a little layer of oil on canvas.

Tuymans: That’s the afterimage of the image. And that’s also the afterimage of the painting, as painting itself. This is becoming more clear and important. Because as time goes by, I distance myself further in order to create the possibility of this reflection, to measure the distance between what I make and what I think. These paintings are all about that.

***

Zwirner: Luc, you are an exemplary artist in that respect. Through these almost 20 years you’ve been incredibly focused, incredibly driven, and, it’s fair to say, endlessly creative. Every time I enter the studio, I enter a new world. But you have also been extraordinarily loyal, a real friend. That’s not something anybody who works in my profession can take for granted. When you get to develop this kind of a relationship over so many years with so many peaks and some valleys, it’s a great gift. Little did I know it would turn into that when I first met you.

Tuymans: The same is true for me. I had a very good feeling when you entered my small studio back then.

Zwirner: Yeah, you were still in the old studio in Antwerp.

Tuymans: Yes, I was and I had a good feeling because I felt that you were serious. I also thought you seemed generous. That’s what I want to compliment you on—being generous. I think that’s very important. And as far as loyalty is concerned, I think it is natural given that the collaboration has been so good, specifically when you rescue works, when you get them out of auction houses. It’s protection and that’s something an artist needs. You do that more than any other dealer I work with. That’s what made me respect you even more. I guess when something is good, you shouldn’t change it. And so we just continue. This is the first part of a good collaboration which will go on and on and on.

Zwirner: Amen.