Over the past two years Gillman Barracks, an old army base, has emerged as Singapore’s new art district. With shopping being the national sport of this island-state, it is no easy matter for an art district to achieve the fame of shopping districts. Say the name of Gillman Barracks to a taxi driver, and nine times out of ten, he cannot properly drive you to your destination; but just mouth the word IKEA, and you would be whisked off in a jiff. What shopping centers sell and what experiences they offer are keenly studied by researchers. And so it is with art — for instance, what exhibitions should be held in a gallery, and what recollections and associations they bring; what viewers take with them and leave behind — these are the reasons why people go and see art exhibitions in galleries.

About a dozen exhibitions recently opened in the Gillman Barracks; all of these relate to painting — naturally enough, for commercial galleries. Among these, Ian Woo’s solo exhibition, coupled with a group exhibition of Indonesian painters at Equator Art Projects, allow us to see the position of painting within Southeast Asian contemporary art and also the positions of the individual artists.

Singapore Gillman Barracks Art district transfered from the former military camp. 新加坡昔日的兵营改造的吉尔曼兵营艺术区

________________________________

Ian Woo, “Dream Sushi and the beginning of independence,” acrylic on linen, 183×147 cm, 2013. Ian Woo,《梦到寿司和独立的开始》,亚麻布上的丙烯画,183×147 cm,2013.

Ian Woo: How I Forgot to be Happy

Tomio Koyama Gallery Singapore (47 Malan Road #01-26 Gillman Barracks Singapore) May 3–Jun 16, 2013

Ian Woo’s abstract paintings impart above all a power of visual imagination as if they — fine multi-hued granules hovering in the zone between black and gray — were suddenly caught up, quick-frozen in a flash, the pigment detonating to unleash its own energy, and spreading in deep diffusions across the canvas; a few yellow-hued wisps bear flashes of fireworks in the dazzling instant between their blooming and extinction while wafting in a transparent grey firmament. Ian Woo’s painting is the transplantation of an abstract sensation from the consciousness onto the canvas, but the ultimate result is a challenge that questions both himself and his viewers. As he himself might say: “Every painting is intuitively built up between the will to realize some sort of mental abstract imagery and that of painting’s negating position to offer something other than what I envision.”

From this standpoint, for Ian Woo to give his own works titles is something of an unfortunate and superfluous error. This entire exhibition is unable to shake off the shadow of its title “How I Forgot to be Happy.” “They Came in from the Sides” has something of the aura of a zombie movie, while “Dream Sushi and the Beginning of Independence” is a clear allusion to the history of Singapore, yet for some reason its precise point is elusive. Discussion of his paintings thus becomes derailed into questioning the meaning of his works’ titles and, as these are abstract paintings, the discussion tends to veer towards the importance of the titles of abstract paintings in general. Rothko’s works only ever permit the pigments on the canvas to convey the theme, all the while leaving the transition from materiality to spiritual experience in the hands of the audience. Thus “Untitled” is a recurrent title in very many abstract artworks, and reflects the possibility of multiple interpretations in the eyes of an audience.

When color and shape smash through the limitations of consciousness in this spiritual medium of art — a medium that lulls the senses and allows an experience of the unknowable to become possible — it would seem important for language to take on a diminished role, especially in the oeuvre of Ian Woo. In the absence of an abstract tradition of painting in Singaporean, Ian Woo’s works bear his own forceful style. An artist who has seen about as many years as this young republic, Woo creates work which is inseparable from his memories and imagination. Though young, he can still bear the weight of his artistic insights and launches many challenges upon the viewer. But silence would have been more appropriate than chatter in this particular case.

________________________________

Ugo Untoro, “Some time in the evening,” Oil on Canvas, 200×200 cm,2013. Ugo Yntoro,《夜晚某时》,布面油画,200×200 cm,2013。

Now! Immediacy in Indonesian Painting

Equator Art Projects (47 Malan Road #1-21 Gillman Barracks, Singapore) May 3–Jun 16, 2013

Painting is for some Indonesian artists a direct and visceral experience, one which relates not only to the transplantation of classical European painting during the Dutch colonial period, but also to native Indonesian culture, Balinese dance, Javanese carving, and Wayang shadow puppetry. All of these make the flourishing of visual arts on Indonesian soil teem with color and movement. The group exhibition by Equator Art Projects is just such a combination of visual and dynamic expression.

Walking into a room hung with paintings in different styles is very much like walking into a room packed with a variety of people. Some will snub you, just as the appearance of others will cause you to stare back at them blankly. But in some cases you meet someone, you lock eyes and exchange a knowing smile. Ugo Untor’s works entered my field of vision in just this way: large patches of damp green, blown from rainforests mantling tropical islets to moisten a world washed with water. This world’s sense of permeability and delicacy is akin to skin that has been rinsed; to pinch it would cause it to produce a rush of blood flowing underneath. The space created on the canvas naturally points to moods, so the red of the beach cross-section engenders a sense of unease and balefulness. The red blank on the canvas below and the graffiti under it creates a sense of doubt and of the “unknown” which seeps into the territory of the viewer’s soul.

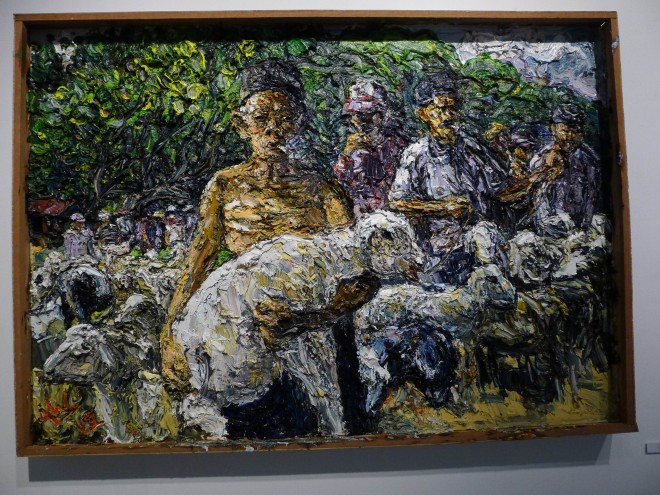

Where Untoro’s work communes with the senses, Awiki’s work uses physical form and texture to rivet the eye. Awiki employs thick oil colors on a huge stretch of canvas, building up layer upon layer to erect veritable ramparts of pigment, so that from up close the man holding a lamb appears to be just a superimposition of various pigments but, if one takes a step back, the image takes on its full form. Full force coheres on the surface of Awiki’s paintings, fully relating to all the actions associated with painting: coating, wiping, stippling, scraping …one may discern traces of pigment lining and furrowing the canvas and their resulting residual textures. In light of the unfettered development of contemporary art, we may question whether or not an aptitude for traditional painting indicates a reversion to old-fashioned ideas but we cannot deny the energy that Awiki’s works exude: it animates the viewing experience into a movement of our own bodies and carries us both into and out of the canvas coaxing us into an elegant dance in front of it.

Perhaps this is due to the urgency indicated in Tony Godfrey’s curation of this exhibition of Indonesian painting. In works of Javanese painter Nasirun, the richly painted surface runs with variegated colors and images, while penetrating deeply into the layers of pigments and forming a subconscious remembrance and/or imagination of the local culture. Such a national theme still lingers among the older generation of Indonesian artists.